Queer and Anti-Colonial Gardening: A Syllabus – M. Ty

The garden is for me an exercise in memory . . .

— Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book)

One cannot rule out the possibility of a connection between . . . two events, or the existence of a hidden link, as one sometimes finds with plants, for instance, like when a clutch of grass is pulled out by the roots, and you think you’ve got rid of it entirely, only for grass of the exact same species to grow back in the same spot a quarter of a century later.

— Adania Shibli, Minor Detail

Gardening has been called the slowest of the performing arts. It’s true—plants most often transform and extend their reach at a pace that eludes immediate perception. Time-lapse photography can speed up their long choreographies so that the eye can catch a glimpse of them. But anyone who has ever put a seed in the dirt and waited for something to happen—wondering if it will, then waiting and waiting some more, within a bouquet of question marks—has some intimacy with that gap between the cadence of their acts and the temporalities of the land’s expression.

The vegetable time of the garden is not only unhurried in relation to the tempos of human perception, it is also intergenerational—sometimes ancestral. When the Caribbean philosopher Sylvia Wynter wrote of the subsistence plots that black captives kept on the edges of the plantation, she noted how they were also places of burial: the squash, yam, and other harvested crops would be gifted as offerings to those who, recently buried, were making the “luminous transition” into the ancestral realm. As spaces of gathering, these gardens could alchemise mourning into militance and incite grief into rebellion.1 That they harboured seeds of radicalism was one of the primary reasons the plantocracy surveilled and tried—never completely succeeding—to regulate them with a desperate paper trail of prohibitions.

The plantation economy drove monolingualism into the throat of the earth, so that the soil could say only one thing: sugar sugar sugar sugar sugar, cotton cotton cotton cotton cotton, indigo indigo indigo indigo indigo. Drawing from the embodied memories of alternative practices of subsistence, enslaved people cultivated gardens that were polyrhythmically polycropped. They did not sow for profit, but for collective nourishment.

These provision grounds were often left unsupervised. Beyond offering food for the belly and a provisional reprieve from the routine brutality of the master, they acted as a portal to another cosmology. Gardening was a practice of remembering how to live otherwise than the laws of capitalist white supremacy dictated. The plots were places for plotting a way to a different world, in the midst of the impossibilities of this one. For these reasons, Wynter calls them sites of “cultural guerilla resistance.”2

This syllabus is designed to amplify Wynter’s insight, and to open the ears wide to the frequencies of possibility that take root in non-normative acts of gardening. Imagine a stalk with two leaves, each with its own direction of reach: one that invites reflection on the way imperial projects have leveraged botanical knowledge for the purposes of indigenous dispossession and global extraction; and another that gathers dispersed practices of gardening which refuse colonial modernity’s exhaustion of land and labour, along with its humourless fetishisation of heteronormative reproduction as the holy grail of social value.

The readings, soundings, video works, and experiments in sociality that are featured in this syllabus come together in conjuring a provisional ground for minoritised horticultures. These resources guide attention towards how these planting practices seed refusals of the sexual, ecological, political, and epistemological norms through which European colonial modernity reproduces itself as an eternal catastrophe. Part of the invitation here is to study the possibility that subsistence grounds contribute to the material basis of what Wynter elsewhere refers to as a “demonic ground”—or the inhabitation of meaning which does not submit to the hegemonic “regime of truth” that presently governs global reality.3

As a kind of initiation into these peripheral grounds, you can cruise this patch of questions:

Recalling that diaspora is rooted etymologically in words that evoke the scatter of spore, how have gardens offered resources for collective memory in the wake of the tremendous displacements induced by (neo)colonial accumulation? And what have they offered by way of therapeutic and medicinal relief?

What are repertoires not only of root-work but of root-play?

What visions are given by the spark between the steadfastness of indigenous plant

knowledges and the various arts of refusing to submit to occupation? What are the primary strategies that settlers have deployed in waging their centuries-long war against black and brown subsistence?

How do gardens act as both an expression and site of queer desire, and in doing so, potentially derange traditional delineations of public and private spheres? What gestures of gardening enact the forms of queer dependency that constitute one of the roots of crip wealth? And which gardens have offered themselves as allies in holding opacity for forbidden contact?

What undictated possibilities of eros and knowledge have emerged from frequenting garden grounds?

Can one think of gardening as a kind of poiesis that isn’t held hostage to conventional framings of the capacity for literacy? What of its rituals activate the radical (a word that derives from “root”)?

How has gardening become, at times, an exercise of liberation—even if only seasonal, partial, or precarious?

What are the strange and stranger fruits of a garden that does not conform?

Groundings

Let’s begin with the alphabet and some story. At the entryway of the syllabus, painter Kara Walker and novelist Jamaica Kincaid greet you. Recently, they collaborated on the making of An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children (2024). The slender, green book proceeds through each letter of the alphabet, elaborating a word related to the garden—with Walker on the illustrations and Kincaid on the word. “B is for Breadfruit. . . . S is for Solanaceae. S is also for Sugarcane.”

Still warming up, you can listen to Kincaid speak about traditions of gardening as an ambivalent inheritance.

If you’re near the Bay Area sometime, you can visit Walker’s installation Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) (2024)—her response to a city that has priced out colour. Extend your hands to receive a fortune that flutters down from her tree-tall automaton’s mouth. Here’s the one I got:

Better and more haunting than the messages tucked inside a fortune cookie.

If you can’t travel, or you’re not allowed to enter the United States, or are choosing to

stay away from its fascist energies, you can catch a remote glimpse of how she started to

devise the installation in this video.

hands in the earth

Ideally, gardening is not only in your head but in your hands—and the generative push of

the soil against them. As the Nishnaabeg musician and artist Leanne Betasamosake

Simpson says in “Land as Pedagogy,” “If you want to learn about something, you need to

take your body onto the land and do it. Get a practice.”4 As you move through the

materials in this syllabus, you may want to plant some actual seeds—even if only at the

modest scale of a single pot. Tending things into growth out of a tiny capsule of life has a

lot to teach, particularly about how tenuous the threshold with non-life can be.

To encounter seeds is to make contact with an intergenerational transmission. Sourcing

them thoughtfully can provide a way to start thinking about what strains of the past you’d

like to cultivate in the present, and what ancestral keepings you’d like to be in material

conversation with.

Some leads about where to find them:

- Vivien Sansour, the keeper of the Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library, imagines the seed as a “subversive rebel,” and also as an inheritance given by “our ancestors throughout thousands of years of research and imagination.” Disarming Design stocks bamyeh (okra), molokhia (which for Filipinx folks might be more familiar as saluyyot), yakteen (gourd), sabanikh (spinach), and other crops. Sansour’s seeds have travelled across the Atlantic to the Hudson Valley Seed Company, which stocks yakteen.

- In the United States, Truelove Seeds has an African diaspora collection, which includes Aunt Lou’s Underground Railroad Tomato, a variety that was carried by a black man from Kentucky to Ripley, Ohio, where there was a safe house on the underground railroad.

- Sistah Seeds, based in Pennsylvania in the US, has a curated catalogue with the intention of “regenerating” seed-keeping traditions of the African diaspora.

- Glass Gem Corn is a stunning crop offered by the Alliance of Native Seedkeepers; they also have a sanctuary that collects ancestral seeds which are not for sale and are reserved for their communities of origin. Purchases from their catalogue support native farmers on Turtle Island.

- Second Generation Seeds carries Asian heirlooms and also offers (radish) colouring books and grower’s guides that put people in touch with the histories of perilla, chrysanthemum, and soybean.

This list skews toward Turtle Island; if you live elsewhere, you can search for local seed-keeping projects closer to home.

As you’re plotting what to grow, you can tap inspiration by reading about the folk gardeners who keep difference alive. In Heirloom Seeds and Their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity, Filipina anthropologist Virginia D. Nazarea follows seedsavers and their practices of staving off the forgetting that is induced by colonial monoculture.

In an interview with artist Marwa Asanios, Samanta Arango Orozco speaks about her work with Grupo Semillas, which supports indigenous and peasant communities in Colombia who are struggling to protect their seeds. She foregrounds the role of women as seed guardians and emphasises how, contrary to the museal logic of the seed bank, they insist that seeds are better off “walking”—that is, out and about, in the ground and among the people, rather than sealed up and stored.

plotting across the black diaspora

In this 1971 essay, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Wynter rereads history in terms of the dualism between the settler plantation and the provision grounds kept by enslaved people: a short, but dense set of reflections.

Gardens make only a small cameo in political theorist Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983). But his larger insight about how “African labor brought the past with it” is worth encountering for anyone interested in problems related to memory, diaspora, and what it is to porter a “previous universe” into a new world.5 These reflections on what has been carried through displacement unfold in the chapter titled “The Historical Archaeology of the Black Radical Tradition.”

The geographer Judith Carney records a moving story—told among maroons—about a mother who, seeing that her daughter will be sold away, passes grains of rice onto her, embedding them within the braids of her hair.

The first two theoretical texts pair nicely with this oral history from Emma Dupree, a virtuosic black herbalist who kept a “garden-grown pharmacy” in North Carolina. At 10:53, she takes the interviewer on a tour through her garden, talking about the medicinal uses of various plants and other personal stories related to her experiences of them. It’s a balm for anyone with a soft spot for grandma energy.

“In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens” is a short but deep meditation by novelist Alice Walker about the complex inheritance of black matrilineal lines of creative power. She sees it manifesting in the garden as an artistic practice—undertaken by black women who were “moving to music not yet written.”

Check out Romare Bearden’s serial garden paintings in homage to “people who can grow things.” This article investigates the woman who likely inspired these paintings.

Romare Bearden, Maudell Sleet’s July Garden, 1985. Collage of various papers with paint, ink, graphite, surface abrasion, and bleached areas on fiberboard.6

imperial phantasies

The next two offerings in the syllabus are companions. In Kincaid’s essay “In History,” her garden instigates a cascade of realisations about colonialism and conquest-by-naming. Though it’s a little sideways, I like to teach this with “She Unnames Them,” a short parable by the visionary of speculative fiction Ursula K. Le Guin.

Botanical gardens are typically regarded as places of leisure. It’s a bit of a mind-fuck to realise how thoroughly they have shaped world history. You can get a glimpse of their role in projects of European domination in the anthropologist Lucile Brockway’s Science and Colonial Expansion (1979). The chapter on cinchona is particularly interesting, as it was instrumental in suppressing the Sepoy rebellion against British colonial forces in 1857.

Curator Sadiah Boonstra’s “On the Nature of Botanical Gardens: Decolonial Aesthesis in Indonesian Contemporary Art” lays out some of the ways that horticultural accumulation was indispensable to the consolidation of empire. She focuses on Dutch extractivism in Indonesia. Her essay also provides an introduction to several Indonesian artists who are working to decolonise the senses. Among the works she speaks about are a short film Hortus (2014), which juxtaposes scenes of botany and pornography. Some of this film was shot in Hortus Botanicus in Amsterdam.

Laguna Pueblo storyteller Leslie Marmon Silko has written a novel that follows two native sisters named Indigo and Sister Salt, as well as a grandmother who knows only one word in English: No. The narration in Garden of the Dunes (1999) follows Indigo as she’s sent to a residential boarding school and later visits gardens in Europe, seeing both horticultural traditions through a comparative gaze.

On the Necessity of Gardening: An ABC of Art, Botany and Cultivation (2021), edited by Laurie Cluitmans, includes an essay by curator and writer Alhena Kastof, which walks through some of Wynter’s ideas about “autochthony,” and also recalls how the authoritarian thugs of the Nazi regime went around tearing up “non-native” species from the “German” soil. They even uprooted Polish forests and replanted them with German flora. This history is a reminder of how fascism gets off on colonial fantasies of purity that traverse the human-flora divide. Amid this fascist milieu, the German artist Hannah Hoch stashed the “degenerate art” that her friends had made deep in the soil of her garden, a story of resistance that is refreshed for the present in an illustrated book called Interior Garden (2024), which is edited by art historian Leah Pires.

“Every Gesture Counts, However Small” is an episode of the podcast Promises, No Promises that revives the intimacy of the epistolary tradition. In this exchange between curator Sonia Fernández Pan and visual artist Karolina Grzywnowicz, their conversation drifts thoughtfully as they speak about the “poetry of vernacular plant names”; the links between racial and botanical classification; and the many unsettling ways that European state forces have deployed plant cultivation a means of camouflaging violence.7 Grzywnowicz recalls how Nazis grew a green belt around their death camps, encouraged the growth of lupine to cover mass graves, and how the commandant of Auschwitz designed his personal garden to obscure his views of the concentration camps. She proceeds to talk about the ways that Zionists have instrumentalised agriculture in the service of Palestinian erasure—not least by planting European pines over depopulated Arab villages.

An (imaginary) inventory of * (palimpsest) plants, gardens, and other related objects* (2021) is a small edition risograph booklet that acts as an interactive guide through the remnants of French colonialism in the city of New Orleans. If you’re in Europe, you can buy it from a beloved little bookstore of mine in Berlin, Hopscotch Reading Room. Otherwise, it can be found online at Constance.

scatter and dia-spora

One of my favourite projects of documenta fifteen was artist Tuân Mami and Nhà Sàn Collective’s Vietnamese Immigrating Garden (2022). They turned their patch of Kassel into a communal space—setting up informal housing for queers who wanted to visit the festival but didn’t necessarily have the funds that could satisfy global north hotel prices. They also worked with the local Viet community to gather a library of seeds and plant a garden together. It was lush, warm, and felt like a green oasis in the midst of a broader cultural landscape that brutally rewards individualism. Newly arrived refugees to Germany also found the space to be inviting and remarked on the therapeutic effect of working in the garden alongside Viet immigrants.

Based in Hanoi, Mami has since dedicated another garden installation to the Viet workers who have immigrated to Taiwan—as refugees from the war of 1979, as brides, imported labour, or as students. Though it’s technically illegal to import seeds, some do so clandestinely, and grow gardens that allow them to feel closer to home while abroad. This iteration of the Immigrating Garden is in homage to Mrs. Dung, who immigrated as a factory worker and, over the years, smuggled enough seeds to start a garden that supports her traditional medicinal practices. This interview with Mami was first published in the “Foreigners Everywhere” issue of Arts of the Working Class, the Berlin street-paper.

The environmental historian Jessica Lee has written a refreshingly readable book about plants, migration, and belonging. It’s called Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging (2025). Alongside reflections about the racially laden terminology of “invasive” species, she also writes about the brassicas that are indispensable to many Asian cuisines, and recalls her experience growing them in communal gardens. She offers one of the rare occasions in food writing in which someone marks a preference for bitter greens over desserts.

In a short reflection on “Touching the Earth,” author, theorist, and educator bell hooks writes of the Great Migration and the ways it induced a lasting estrangement between black people and the land. Overcoming her feeling that she could not garden, she grows some collards and senses how making a meal from what one grows provides a form of ancestral connection.

Inspired by author Octavia E. Butler’s Earthseed series, futurist Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri reflects has designed seed libraries that can be worn on the body.

healing

Aster of Ceremonies: Poems (2023) teaches of that threshold where “master,” by the slightest metamorphosis, becomes aster, a flowering plant. Artist, musician, writer, gardener, and proud stutterer JJJJJerome Ellis gives gorgeous poetry to the flora that runaway slaves would likely have encountered while in flight. The lyrics are steeped in archival material—particularly the advertisements that, like “wanted” posters, gave public notice of captives who had fled and could be identified by their stammer. Aster of Ceremonies is incantatory—elegiac and honorific botanical music that nourishes collective tropism towards the dead. Listen to dysfluency become chorus. In the audiobook, Ellis performs the music that is transcribed and canted on the page. She can also be spotted in this video, playing the saxophone to the plants that are growing along the High Line in New York City.

The Yogyakarta collective Lifepatch has devoted this videowork to Batak healing practices and medicinal plant-knowledges that Dutch colonists targeted for elimination.

In one of the capacious moments of poet Roger Reeves’s essay about black men at rest, he reflects beautifully on a lesser-known side of the rapper DMX, who once appeared on the TV show Fresh Off the Boat, in the space of a greenhouse, where he gently lavishes his attention on orchids. He has names for each of the plants (Beatrice, Denise) and elaborates his erotics of care: “You don’t need to give your girl a gift; you need to give her your time.”

As a complement to calls for land repatriation, native people have been advocating for seed rematriation. The Indigenous Seedkeepers Network has been working to release seeds from seed vaults and return them to tribal communities that have an ancestral connection to them. You can read about one of these family reunions that took place in Taos, New Mexico. Mohawk seed guardian Rowen White, who has said that bringing seeds home has been one of the most healing dimensions of her activism, offers a holistic, online course on seed stewardship.

What’s being restored is not just seeds but kin and the practices of planting that, unlike monocropping, don’t normalise ravaging the earth. In Braiding Sweetgrass (2013), scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer recounts the significance of the three sisters way of planting—a method of growing squash, beans, and corn in proximity, so that they all offer some support to one another. If you haven’t already read it, “The Grammar of Animacy” is a memorable chapter—and one that students love.

agri-cultures of refusal

I like Jumana Manna’s film Foragers (2022) so much that I feel compelled to include it, even though it moves beyond the topos of the garden into that of the forager. The film follows Palestinians who defy the Israeli ban on foraging za’atar and akkoub (wild greens that are nutritionally dense and have thorns that soften if you know how to handle them).

Brooklyn-based independent publisher Wendy’s Subway recently released an illustrated book that remembers the story of Abu Jildeh, a band of Palestinian farmers in the Nablus area who staged an insurgency against the British occupation.

In Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (2018), Monica White, professor of environmental justice, assembles an archive of projects that sought to establish self-determining food systems for black communities. Among these include activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s freedom farm and garden, which she started after federal policies attempted to sever black agriculturalists from their land.

Art historian and photographer Jill Casid considers the cultural significance of the gardens that enslaved people kept, with special attention to their relation to the visual genre of the picturesque and to colonial ideas of hybridity. A good part of Sowing Empire (2004) attends to the role of botanical life in the Haitian revolution. There’s some particularly good lore in there about poison and setting colonial infrastructure on fire.

earthly transitions

An artist who thinks about how to transition out of cultural attachments to the “human,” Precious Okoyomon works with the invasive plants that many ecologists abhor. Their practice is devoted to the “blackness of the earth.” You can listen to their Reading to Plants (2020), which they performed in one of their verdant installations that mess with the typical sterility of the gallery space. You can also read about the garden they cultivated in the Nigerian Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, which they describe as a “love letter to Lagos.”

Another Mother is a database that gathers information about plants—as well as fungi and other creatures—who live out multiple sexes, contrary to the silly proposition that it is “natural” to inhabit one biologically determined gender forever and ever (a credo of contemporary anti-trans legislation).

In this corner of Transgender Studies Quarterly Now, you can read about the collective farm called Urban Campesinx, which hosts two-spirit ceremonies and cultivates Cempasúchil (marigold) as a way to honour queers who have died while in detention.

Here’s a zine called The Transgender Herb Garden: An MtF guide to disconnecting one’s self from big pharma.

In a piece called “Necrolandscaping,” Casid writes about the Transgender Memorial Garden.

Run by trans and two-spirit folks, Mariposas Rebeldes started a communal garden in Atlanta to address food scarcity and apartheid. One of the cofounders, Wvto Tristán, is restoring connections to crops and companion planting methods that were significant to their Náhuatl ancestors. They collaborate with the Trans Housing Coalition and create spaces where trans POCs can find nourishment.

pleasure gardens

Burn something that smells good and treat yourself to a listening session of pianist and polyrhythmic poet Cecil Taylor’s Chinampas (1987), which is inspired by the pre-Columbian “floating gardens” of the Valley of Mexico. You can read a little about this agricultural craft in this Scientific American article. Fans of Taylor can go on and read Fred Moten’s lyrical tribute to him—and all that is “transmitted on frequencies outside and beneath the range of reading.”8

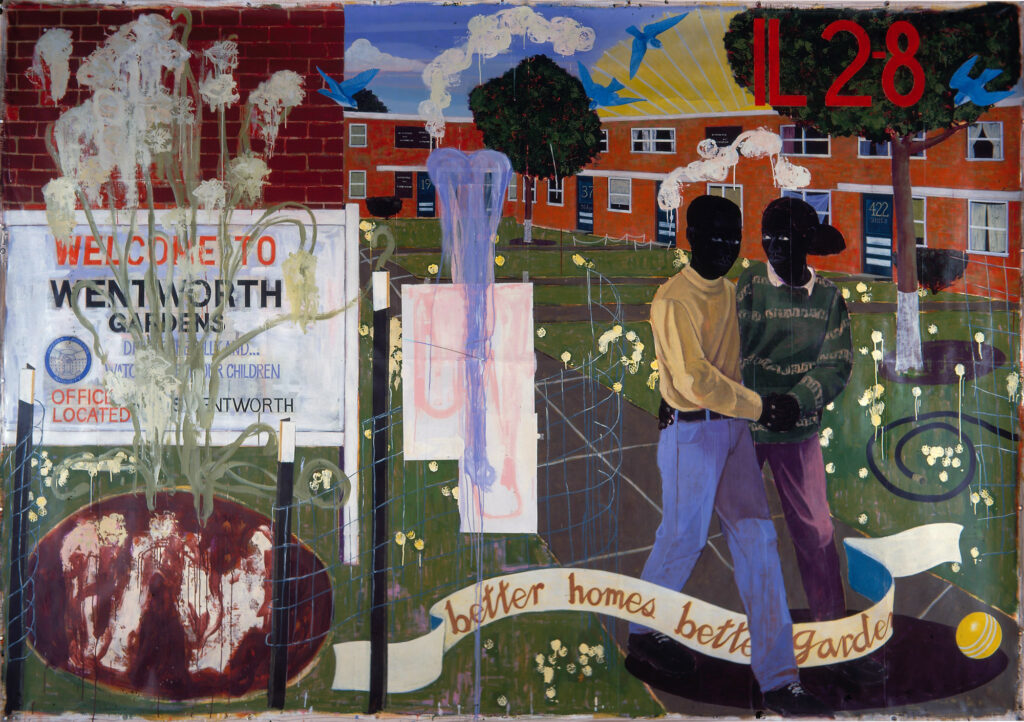

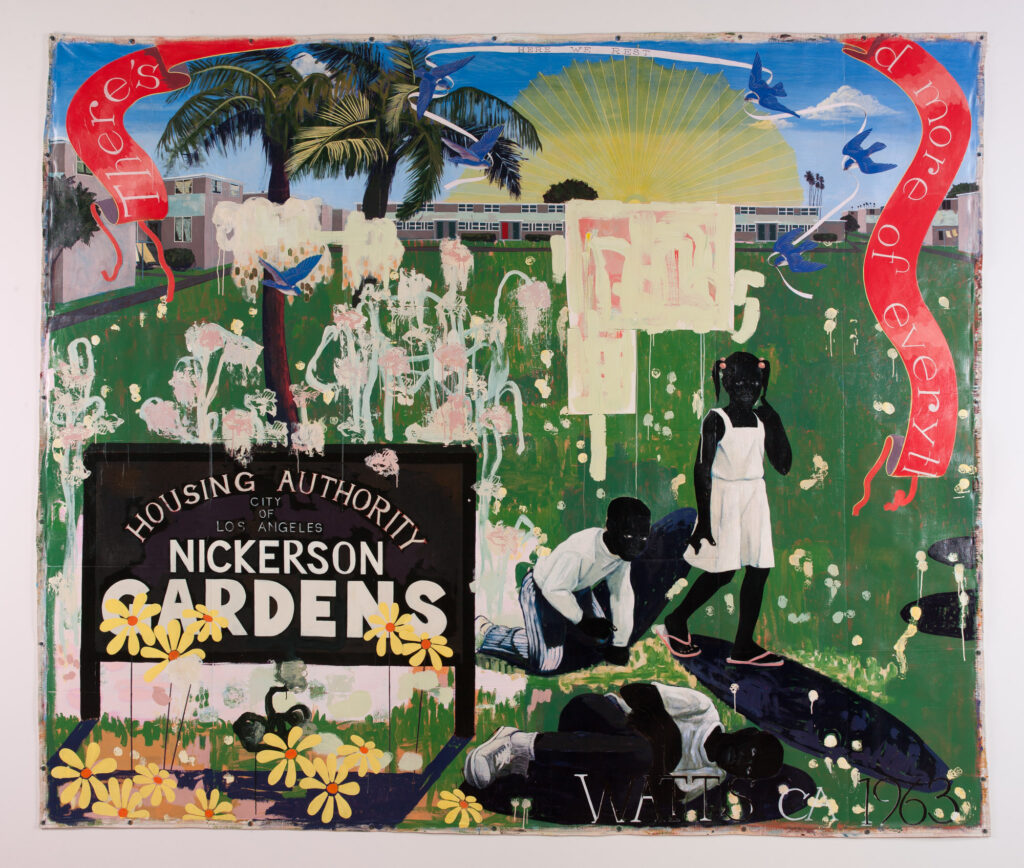

You might then spend some time cruising all the compelling details within the series of mural-scale paintings that artist Kerry James Marshall refers to as his Garden Project. There are the dripping clouds, the layer of cellophane through which the stuffed rabbit sees the world, and the bluebirds beaking old-school ribbons of text across the sky. Playing with the double meaning of “projects,” he dedicated these epic canvases to black working-class neighbourhoods in Chicago and Los Angeles, including the one in Watts, where he grew up. Refusing the white liberal gaze that would see these spots exclusively as places of indigence, he wanted to beam attention onto the ways people “experience pleasure in the projects.”

© Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Kerry James Marshall, Many Mansions, 1994. Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas, 289.6 × 342.9 cm (114 × 135 in.)9

© Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

AIDS activists Dont Rhine and Marco Larson formed a sound art collective that put together a compilation called Second Nature: An electroacoustic pastoral (1999). Some of these tracks include recordings from the 1998 occupation of Griffith Park in Los Angeles. Ultra-red and the Gay and Lesbian Action Alliance collaborated in reclaiming the park, which was a spot where mostly black and Latinx queers pursued their pleasure in public. A homeowners association wanted to “rid Griffith Park of the gays.” The Los Angeles Police department did their bidding and subsequently raided the beat.

It works to read that alongside cultural theorists Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner’s essay on “Sex in Public.” That piece couples well with queer writer Amalle Dublon’s reflections on Ultra-Red and states of dependency, which will also bring you to hear the R&B group TLC in ways you never have before.

Many of the arguments that Berlant and Warner make in an academic register are voiced in this interview with pop star George Michael, during which—palpably fed up with the homophobia of mainstream media—he talks about cruising at London’s Hampstead Heath. He finishes with a diatribe that elaborates how exhaustingly annoying gay respectability is. “I don’t expect straight people to understand,” as he says.10

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Farzad Owrang.

Salman Noor’s Night Park (2022) is an homage to brown people cruising and finding erotic refuge among the leaves. The painting has a different colour palette but nevertheless hosts palpable echoes of Hieronymous Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1503–1515). It was shown at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, as part of the exhibition Seven Rooms and a Garden, which ran in 2023 and 2024. Oil on linen, 170.2 x 307.3 cm.

In the final years of his life, the filmmaker Derek Jarman cultivated an idiosyncratic garden as he was getting worn down by AIDS. The spot where he worked and ornamented the land with his elegantly scrappy sculptures was near a nuclear power station. If you’re ever nearby, you can visit Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, at the bottom of the UK. Otherwise, you can read his journals, in which reflections on gardening and dying grow through each other. His friend Howard Sooley took a series of photographs of Prospect Cottage across the seasons, which are gathered in Derek Jarman’s Garden (1995).

continuing education

A hub for black, indigenous, queer, and trans herbalism, Herban Cura hosts a living library with many wonderful knowledge-shares that connect people to ancestral, ecological wisdom and ways of living in solidarity with more-than-human kin. Their 2025 line-up includes teachings on the ancestral plants of Palestine, opium medicine, and the Trinidadian folk figure of the “soucouyant”: a creature who transforms from an old woman and sheds her skin to become a ball of fire.

passing the hat

If you have taken something from this syllabus and wish to offer something to back to the earth, please consider donating to Thamra, a gardening initiative that is working to feed and sustain people in northern Gaza. It was started by the farmer Yousef Abu Rabee, who somehow managed to grow food between bombed-out buildings and endless rubble. On 21 October, 2024, an Israeli drone strike assassinated him while he was distributing seedlings to his neighbours in Beit Lahiya. He was martyred near his nursery.

M. Ty is an ember of a diaspora. They are an Assistant Professor of Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

- Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, 77, unpublished manuscript, no date, housed in The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York,

https://monoskop.org/images/6/69/Wynter_Sylvia_Black_Metamorphosis_New_Natives_in_a_New_World_1970s.

pdf. ↩︎ - Sylvia Wynter, We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk About a Little Culture (Leeds: Peepal Tree Press, 2022), 292–295. ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter, “Beyond Miranda’s Meanings,” Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean Women and Literature, Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Savory Fido, eds. (Trenton: Africa World Press, Inc., 1990), 356. For an exfoliation of Wynter’s notion of the “demonic ground,” which is partially borrowed from physics, see Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). ↩︎

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, no. 3 (2014), 17–18. ↩︎

- Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 122. ↩︎

- [Image not reproduced due to rights restrictions — see article linked above.] https://www.southerncultures.org/article/in-search-of-maudell-sleets-garden/ ↩︎

- Sonia Fernández Pan and Karolina Grzywnowicz, “Every Gesture Counts, However Small,” 15 April

15, 2024, produced by the Institute Art Gender Nature HGK Basel FHNW, Promises, No Promises, podcast, 1:24, https://dertank.ch/we-explore/podcast-promise-no-promises/. ↩︎ - Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 41. ↩︎

- he painting referenced here can be viewed in https://art21.org/read/kerry-james-marshall-many-mansions/ We are unable to reproduce it directly due to image rights. ↩︎

- George Michael, interview with Nina Hossain, July 27, 2006, ITN Archive, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVJPY3dpA38. ↩︎

- Break Down, Or: Dismantling the House that Narrative Built – Moosje Moti Goosen

- notes towards an otherwise – gervaise alexis savvias

- A Young Cowboy First Saw the Lights: Part 1 – Philip Coyne

- Open Glossary for Queer (immaterial) Architectures – die Blaue Distanz

- BLACK HOLES MATTER! – Yangamini

- Queer and Anti-Colonial Gardening: A Syllabus – M. Ty

- Plot(ting): Practices of Ambiguity — Patricia de Vries

- Cartas de Agua – Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás

- “Raised on Foundations of Slime” – Amelia Groom

- For a Possibility of Care, Not Ownership – Mariana Balvanera