BLACK HOLES MATTER! – Yangamini

SELL YOUR FART! BUTT PLUGS AGAINST GAS DRILLING! BLACK HOLES MATTER!

Yangamini interviewed by Amelia Groom

Yangamini (“holes” in Tiwi language) is an art collective founded in 2022 by Crystal Love Johnson Kerinauia, aka Aunty Crystal Love, a Tiwi-Warlpiri Sistergirl elder and iconic drag artist residing between Darwin (Larrakia Country in so-called Australia’s Northern Territory) and the nearby Tiwi Islands (known as Ratuati Irara–“two islands”–in Tiwi).

In the collective’s words, “Yangamini strengthens gender-fluid bush knowledge and challenges missionary sexual oppression, rentier violence, racialised governance, economic control, rhetorical sustainability, and mining extractions in the settler Northern Territory.” Connected through “Tiwi, Gulumirrgin, Warlpiri, Kunwinjku, Yolŋu, Wardaman, Karajarri, Gurindji, Burarra, Minjunbal, Bundjalung, Mununjali and other extracted lands and seas,” Yangamini “accommodates First Nations sexual minorities who seek refuge from the rigid gender customs of mainland communities.”

Aunty Crystal Love first got into the drag scene and came out as a trans woman in Sydney in the 1990s. She eventually moved back to the Northern Territory, where she had grown up. Writing for the free Darwin magazine GayNT back in 2000, she reflected on how anti-queer discrimination and violence had been introduced to Aboriginal communities through colonial regimes of dispossession and imposition: “If you go back, it mainly started with the missionaries . . . they brought new prejudices and new judgments. They liked to tell my people what was bad and what was good. They tried to wipe out our culture and our beliefs. The white man’s religion changed the way our people think.”1

In the decades since, Crystal has become a legendary advocate for queer and trans communities on Tiwi, and a mentor for younger Sistergirls and Brotherboys–LGBTQ+ people traditionally known as yimpininni in Tiwi. In 2012, she was elected to the Tiwi Islands Regional Council, becoming the first trans woman in the Northern Territory to be elected to any tier of government. Besides touring her drag act around Australia, she has also travelled internationally for AIDS awareness work. She has shared her story in anthologies including Nothing to Hide: Voices of Trans and Gender Diverse Australia (2022) and Colouring the Rainbow: Blak Queer and Trans Perspectives (2015)—and she has appeared in documentaries including SISTAGIRL (2010), BLACK DIVAZ (2018), and Sistagals: Australia’s Indigenous Gay and Trans Communities (2018).

“Sistergirl” and “Brotherboy” are terms from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures for queer and gender-diverse people, including people who also identify as trans and/or nonbinary. In a recent interview, Crystal recalled that she first encountered the terms coming from the aftermath of the Stolen Generations. [For international readers, this refers to the generations of Aboriginal children who were kidnapped by the state and taken away from their families, communities, Countries, and kinship systems to be adopted into white settler families and institutions where they were prohibited from speaking their own languages and practicing their cultures—this was carried out as official government “welfare” policy for genocidal white assimilation from the nineteenth century until the 1970s.]

According to Crystal, people from the Stolen Generations began using terms like “aunty,” “uncle,” “brother,” and “sister” expansively and creatively, in part because they were not allowed to know who their blood relatives were. She remembers how her mother called her butch lesbian friends brothers, and how those butch brothers were uncles and fathers to Crystal when she was a kid. Later, she says, the terms Sistergirl and Brotherboy emerged in specific ways within Aboriginal LGBTQ+ communities, as terms that carry a strong emphasis on queer relationality. In Crystal’s words, “it connects people from different backgrounds to be related. And so I used that terminology because every gay people are connected in some way.“

Yangamini was founded after a major protest, at the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory, against the oil and gas giant Santos and its Barossa Gas Project. In development since 2004, this $5.8 billion offshore project involves drilling into the seabed and laying hundreds of kilometres of pipeline under the Timor Sea, north of the Tiwi Islands. It’s part of a long line of exploitative colonial schemes by extractive industries in the region, and Tiwi Islanders, including Crystal Love, have spent years protesting the project, which poses devastating threats to the area’s sacred ancestral and ecological worlds and knowledge systems.

The night after the Supreme Court protest in Darwin, Crystal Love dreamed of a mythical spirit called Mapurtiti Nonga or Evil Ass Ring, who talks “bad gas” out of its “mouth like a bum hole, created by evil and greed.” The bad gas from the Evil Ass Ring spreads and moves through bodies—“out the ass of one human who passed it onto the next”—infecting everyone with the fart of colonial toxicity, contagion, and perpetuation. (A fuller account of the dream appears at the end of this interview.) And so, Yangamini was formed. The name means “holes” in Tiwi, and the collective’s handle on social media is @black.holes.matter.

I first met the artists in early 2024, at the 24th Biennale of Sydney (Ten Thousand Suns, curated by Cosmin Costinaș and Inti Guerrero). Yangamini was there as one of the exhibiting artists, showing a series of giant butt plug sculptures made with materials collected from Larakia Country and Tiwi Country. [Again for the World Wide Web readership: the concept of Country in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures relates to notions of place and land (what is known in North America as a Land Acknowledgement is, in so-called Australia, called a Welcome to Country or Acknowledgement of Country)—but the concept of Country exceeds settler senses of place and land; it involves complex understandings of ongoing, embedded, reciprocal connectedness to ancestral grounds, waterways, seas, skies, ecologies, and situated cultural practices.]

Butt plugs against fracking; butt plugs for plugging up the huge murderous holes drilled into Country by gas extraction corporations; butt plugs for blocking the insidious Evil Ass gases of extractive coloniality. A week before the Sydney Biennale opening, Yangamini premiered one of their butt plug sculptures, Crucifix Buttplug from the Post-Missionary Culture of Shame and Bribery, Sexual Violence and Privatised Kilinjini (Swamp) (2024), as part of the Biennale’s float for the 2024 Sydney Mardi Gras parade. [Sydney Mardi Gras is an annual LGBTQ+ festival that began as a protest, which was met with police brutality, in 1978, on the anniversary of the June 1969 Stonewall riots. Initially falling in synch with what became Pride in the Northern Hemisphere, Mardi Gras was later moved to February for the Southern Hemisphere summer. As has perhaps become evident, I am using grey where I am adding context for an international readership.]

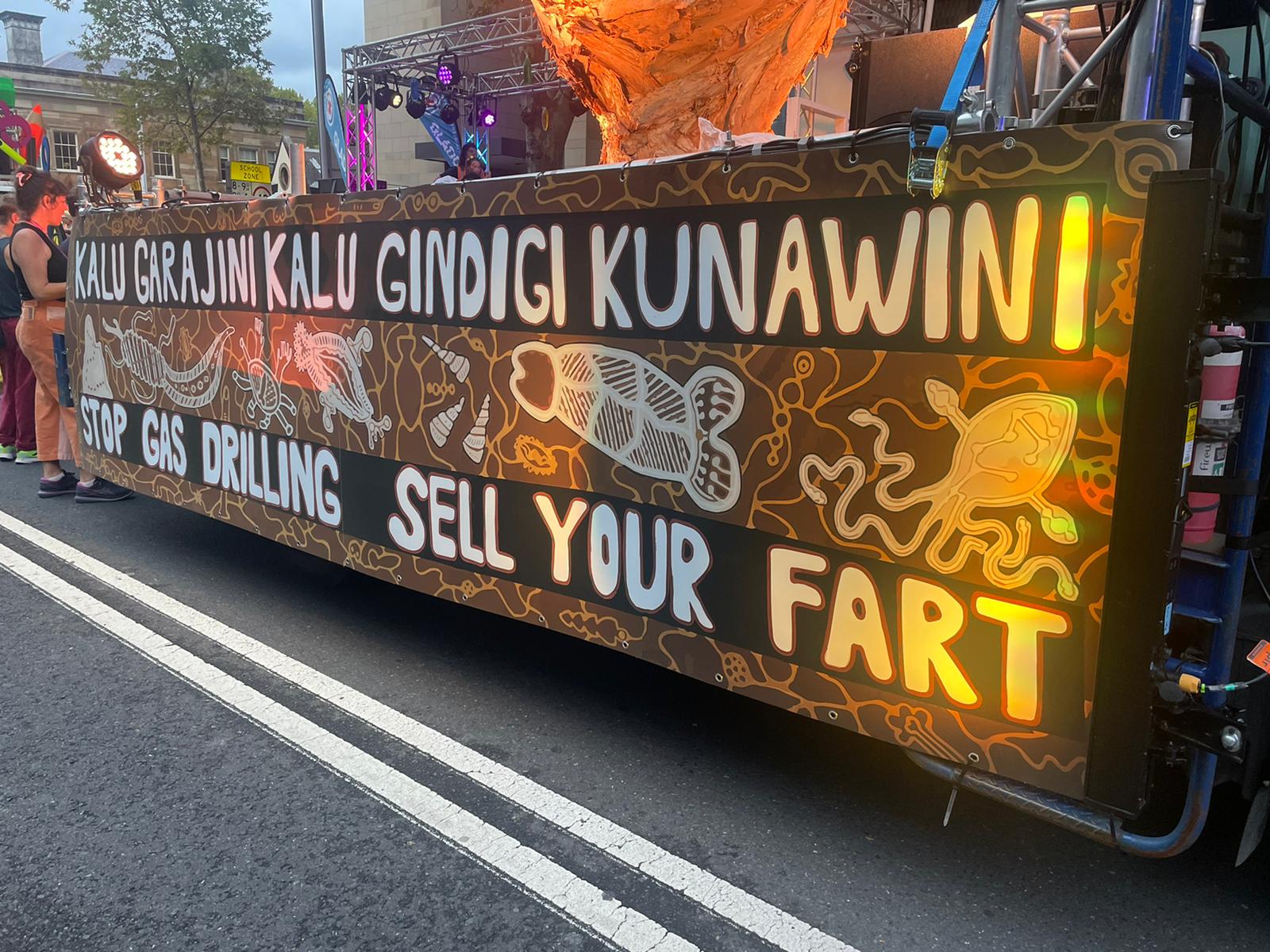

Featured at the top of this text is Yangamini’s video work Mapurtiti Nonga—Evil Ass Dreaming (2024), which was first presented, across eight monitors, at the Biennale. The video includes footage of Crystal Love gracing the Mardi Gras float alongside Robert Cole, twin brother of the late Malcolm Cole, an Aboriginal and South Sea Islander dancer who died from AIDS-related illnesses in 1995. In 1988—as the nation was celebrating its bicentenary, 200 years after the arrival of the First Fleet from Britain—Malcolm Cole led the first Aboriginal float in the Sydney Mardi Gras. He dressed up as Captain Cook, the British naval officer who first paved the way for the colonisation of the land now known as Australia. For the 2024 Mardi Gras, Robert Cole paid tribute to his twin brother in a recreation of the Captain Cook drag costume, sitting next to the one and only Crystal Love. A banner by Yangamini donned the side of the float with the words KALU GARAJINI KALU KUNAWINI / STOP GAS DRILLING SELL YOUR FART.

I marched with them in the parade; it was beautiful. Later in the year, when Plot(ting) editor Patricia de Vries invited me to help with commissioning some new content for this online platform, I immediately thought of Yangamini. The interview presented below took place in November 2024 as a four-way phone call between myself, Aunty Crystal Love, and two other members of the collective: Nadine Biriimilunngga Purranika Lee (an artist from the Larrakia, Wardaman and Karajarri peoples of NT and WA) and Jens ‘Johnita’ Cheung (a chosen daughter of Crystal and “a settler migrant living in Gulumirrgin, who . . . heats up their oxymoronic identities like leftover stews: Hongkong guerrilla, queer bureaucrat, global north environmentalist, ethical quantum computing researcher, arts professional, and other emerging canned food.”)

While finalising this text for publication in May 2025, Aunty Crystal Love was admitted to the hospital for a series of surgeries to treat an infection. She lives with diabetes, a disease linked to socioeconomic deprivation, which has reached epidemic proportions in remote Aboriginal communities. A previous infection led to her having a leg amputated. A fundraiser campaign has been set up for her recovery—please consider contributing via this link.

[Nadine and Johnita are on the phone first; there’s initially some confusion about where Crystal is. She might be taking a nap? Johnita makes some calls and tracks her down; she’s at the shopping centre. They manage to get her on the phone with us…]

Amelia: Ok, hi everyone. Are you at the shopping centre, Crystal?

Crystal: Yeah, I’m spoiling myself for Christmas, baby. How are you going? Merry Christmas, what’s happening?

Amelia: Oh, you know, it’s wet here in Gadigal Sydney, very muggy outside.

Crystal: Oh, don’t you worry, you’d be sweating here [Crystal is in Darwin in the tropical North].

Amelia: I hope the shopping centre is air-conditioned.

Crystal: It is. You know, you sweat your curly bits, but yeah, it’s ok. It’s packed to the max here, yeah, Christmas shopping, shop ‘til you drop.

Amelia: Well, if everyone is here, the first question I have for you all is about how Yangamini formed, how you all came together.

Johnita: You go, Crystal. How Yangamini started.

Crystal: Yangamini started on Tiwi Island. We were looking for people to try and start up something for the girls, for the LGBTQ+ community. We were talking: me, Nadine, and Johnita. And I said, “You know what, we need to start something for the girls,” because it’s like, there’s no employment, we’re talking about housing, we’re talking about a lot of issues; mental health, suicide, everything all together.

And so we thought of this thing called yagamini. A hole. You know, a big hole, a little hole . . . you dig a hole. Somebody said to me, “Why do you call it Yagamini?” And I said, “Well, it’s a hole.” And they said, “What do you mean a hole?” Well, I said, “A hole has a soul.” I remember, my grandmother said to me: “Yangamini, you can do a lot with the hole.” There’s all sorts of holes, people don’t know that. You dig it, you can bury in it, you can cook in it, you can grow things in it. And it represents the earth. For us Tiwi people, we sing for the dead and sing for the living. And I said, “This is part of our culture, it’s part of the nature that we do.”

Conservative Tiwi Islander people were complaining about the name Yangamini, and I said to them, “It’s a spiritual hole.” A person is like a hole, a hole has a soul, every living creature and every human being. In Tiwi society, we’ve been brainwashed by, you know, by people and by Christianity. We don’t go back to our hole beliefs. Why the hole is really important. And I went to those old people, the conservative people, and I dug a hole. And I said, “what that hole represents to you?” And the old people said to me, “It’s just a hole.” And I said, “Well, the hole has something.” That hole there, guess what: I can cook something in that hole, put firewood. That is a living being. It’s from Mother Nature. It’s from the earth. That’s how we’re going to go back to the earth. In that hole.

Amelia: I love your Instagram handle: “black holes matter.”

Nadine: All holes matter!

Jens: All holes matter [laughter].

Everyone: [Laughter].

Crystal: We use that concept of the hole for our Indigenous people to understand that we have to keep our culture and our heritage. If we lose it, then guess what, we have to bury you in that hole and all will die with all the old people. And that will happen. It’s happening now. And you know what I said to people? “If you want to keep a culture strong,” I said, “when you dig that hole, and you cover it, you plant the seed.” That is for us, Tiwi people, for everybody. No matter what sexuality you are, you are part of this. You are part of the cycle and the system. I always use The Lion King, you know, the circle of life [Crystal starts singing “The Circle of Life”], but anyway, it’s the circle of life. And that circle, it represents a hole. It represents us as human beings and our culture, it revolves around the circle.

We are suffering in this community [Crystal suddenly breaks off to greet to people she has bumped into at the shopping centre–there are lots of voices at once, including kids screaming, and voices moving between English and Aboriginal languages]. We need to ground ourselves and find ourselves. Without us being who we are, we will lose everything. Everything will go. And there is nothing that we can do when it’s gone, when most people are gone, when they die in that hole, when they bury them, then that’s it. Nothing won’t be the same. We are forgetting our people and our ancestors, what they left us, you know.

I always tell my family, “You think that you may know that knowledge, but that knowledge comes within ourselves.” That soul, you have to reach it inside yourself. And a lot of people don’t understand. These young ones are modernised. Young people, they say, “Oh, it’s just old, old, dead people stuff.” And I said, “Well, guess what. All the mob people are dying. [Crystal stops to greet someone else she has bumped into at the shopping centre: “Hello darling, thank you”]. They are dying, and we’re going to lose everything. We’ll be in textbooks, and we’ll be losing our culture and practice and we’re all going to die with it. They say, “We have to go with the changes.” But I say, “Let’s still keep our culture.” Yeah, that’s what I said.

Amelia: I remember this wonderful phrase “a hole has a soul” from when you spoke on one of the panels during the Sydney Biennale, Crystal (Mapurtiti Nonga(Evil Ass Dreaming): Scientific Extractions, Sex Capital & Farty Spirits from Settler Northern Territory). Yangamini talks about holes left in the ground by mining corporations—holes of destruction, displacement, dispossession, open wounds on Country, holes to block and heal with giant butt plugs. But you were also getting at holes and connection; holes with souls; digging a hole to make a fire; digging a hole as a burial ground; digging a hole to plant a seed; the watering hole as a gathering ground; and, of course, holes for sexual pleasure and experimentation and play. The hole in this sense is not an absence. It’s a space that holds. The hole as a zone of feeling, sensuality, a space of gathering. I’m reminded of a line from the artist Pope.L, who worked with something he called “Hole Theory,” insisting “LACK IS WHERE IT’S AT.” The hole is not emptiness; it’s possibility and abundance.

Crystal: It is abundance. I learned that from my grandmother. It was a concept that came to me. Yangamini was born because the ancestors gave me the idea. They wanted us to keep the creation going. We are too greedy in this world. We want to conquer. We want to divide. And guess what, we forget about who we are. When we die, you still have to practice. We teach others; that’s how we learn. Yeah, and the thing is, if I die, Johnita is the daughter to carry my legacy. It’s like passing my legacy onto others; it’s the culture that I teach Johnita. But the state we’re living in now, it’s like, culture, religion: it’s all for decoration, it’s all to get what you wanna get. You get money, and you get fame, and you get all these things, but you gotta realise that it’s your spirit dwelling that connects you.

When you dig a hole, you make a fire for a smoking ceremony. And when you dig a hole, you can feel the ground. You can feel Mother Nature. You can feel the spirituality. When you bury people, when they put the coffin down, you feel that spirit is pulling in, when we start singing and dancing . . . [Crystal breaks into song.] And they really feel—that person in the ground—they feel when they’re going down, they are going for good. But guess what, when you go in that hole and you’re buried with the dirt, your spirit is free, and you go back to your homeland, yeah.

And we made the butt plugs, you know—you poke yourself with a dildo, and you can feel the pleasure, going in and out the hole. Your body tells you, and it’s exactly like that, in a spiritual way, yeah. It can be sexual; it can be healing . . . If the others wanna speak, I’m out of breath now. Do you get the picture, where Yangamini comes from?

Amelia: Thank you, Crystal. Nadine and Johnita, maybe we could talk about the sculptures you made for the biennale. Tell me about the giant butt plugs and how they are imagined as part of your collective resistance to the violence of extractive industries on Aboriginal land.

Nadine: Yes, well, they’re digging great big holes in our Country right now with all the fracking. They penetrate into the ground, and they explode in it, and, yeah, they’re basically fucking us! They’re killing us. We are sovereign to this Country, and we are the custodians of the Country. Slowly, through all the policies and everything else, they fuck us over. They’re illegally on this Country, and if you follow the money, you see them killing the people, doing ethnic cleansing to the people who are the sovereign owners. And this is what we are responding to with the project as Yangamini. With the butt plugs we made, the specific materials reflect different things, and I think Johnita can go into the intricacies of that.

Johnita: Oh, Crystal is cut off now, there’s a storm coming and she got disconnected. Anyway, yes, this new gas project will pipe into the middle of Larrakia Country, so this is a struggle that affects everybody here. For the butt plugs, we chose materials that are inherently troubled in settler colonial politics. The tallest one is made from Carpentaria palm, which we saw a lot of outside the Northern Territory Supreme Court during the anti-gas protests back in 2022 when Yangamini was forming. It’s a palm tree found in Yermalner (Melville Island), where Crystal’s clan is from. It’s called jora in Tiwi. But Crystal and others from the Kerinaiua family group couldn’t recognise the palms outside the court. Her people were relocated 100 years ago to the Wurrumiyanga Catholic Mission on Nguyu (Bathurst Island). The palm was traditionally used for weaving and making vessels for carrying food and water, but through the history of colonial displacement, a lot of the traditional knowledge around it was lost.

And then in the rebuilding after Cyclone Tracy [a devastating cyclone that hit the region in 1974], you start to see Carpentaria palm becoming popular for people’s private gardens in Darwin. You know, the “rentier colony”: taking over the land but still wanting to look tropical and blend in like a local. And then, because everyone grows the Carpentaria palm in their gardens, it ends up producing all this green waste landfill because the giant branches fall every wet season. And now we’ve got chemical engineers from Charles Darwin University turning palm waste build-up into biofuel energy. They have reached out to us wanting to turn Tiwi plantation wood into military jet fuel for so-called “community income.” So the Carpentaria palm really entangles histories of extractions, including missionary destruction of local knowledge, settler colonial design aesthetics, and the ongoing US military presence in the region.

Then there’s the termite mound butt plug. We collected a lot of the material around the airport in Darwin, which started as a military base on unceded Gurambai (Rapid Creek River in Gulumirrgin Country) and then became a commercial airport. Even now, it’s the only airport in so-called Australia that runs 24/7, for military purposes. When you arrive at Darwin Airport, you see these wooden carved Tutini, Tiwi Pukamani poles outside as a welcome [Pukamini is a multi-phase death ceremony which includes the placement of Tutuni grave-posts at the burial site]. I find it so deranged, like; why would you use something so significant from a ceremony, and especially from Sorry Business, to welcome visitors to an unceded Country? [Sorry Business refers to death and mourning-related ceremonies, responsibilities, and traditions in Aboriginal cultures.] Anyway, when you look at these poles at the airport you can see they are being eroded by termites. The airport itself is built from metal, so nobody really cares that you’ve got termites right here because they’re not going to have any effect on the airport operations.

We also sourced from termite mounds around Channel Island Power Station, which is part of Gulmerrogin Country. Nadine and I have been spending time there doing some filming. That’s where they will build the petrochemical precincts to receive and process the Barossa Gas extractions from Tiwi Sea Country. I hooked up with someone from the military, and they told me how they are planning to use a pesticide product from BASF in Germany, the largest chemical producer in the world, to kill the termites at the military base. And it’s interesting, because right now, with Russia invading Ukraine, we’ve got a global gas supply shortage, and that shortage is used by a Japanese corporation to lobby the government here and get approval for what they want to do around Tiwi with the Barossa Gas Project. But who blew up the Nord Stream pipelines? I believe it was the US. They’ve become the biggest liquified natural gas exporter in the world right now, following the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines. And it’s the same type of gas that they want to drill from Tiwi. The chemical giant BASF is suffering from gas shortages in Germany, so maybe they have to slow down killing termites around the airport, the militarised panopticon, to protect resource extraction in the northern colony of so-called Australia. Also, one of the traditional uses of the termite mound is to treat diarrhoea, and with Yangamini, you know, we are talking about trying to stop all the bad military shit from coming out of the hole [laughter].

There’s another butt plug made with a blend of materials from the coast. Nadine and I have been spending time at Binybara, which is Lee Point, where they have a company building new military housing. They chose this pristine coastal bushland area, which is sacred for Larrakia peoples, which has trees older than the colony of Australia, and they’re bulldozing it to make 800 military houses. Actually, it’s a commercial enterprise to sell housing for profit. Nadine’s daughter, Cyan Sue-Lee, started the petition for returning Lee Point to the care of the Larrakia people, and you can see all these racist comments on Facebook with people saying they think everything will be taken by First Nations people. This is the perpetual settler mindset: everyone wants their own property on stolen land, and everyone is supposed to follow the same logic for “moving forward” as a nation. This self-colonised notion of liberation through property ownership comes from John Locke in the seventeenth century and is still very much thriving, especially under the brutal history of Australian “terra nullius.”

It’s the same on Tiwi Island; when you arrive at Wurrumiyanga, you are welcomed by all these missionary houses right at the front line. They cleared the ancient mangrove areas so they could have a better coastal view, and now that is causing shoreline erosion and collapse. In the eyes of some elders, it’s the killing of the creation story figure of Mudungkala, who came from the ground and, with her body, formed the Ratuwati Yinjara (“two islands”). You see this everywhere in Larrakia Country too; it’s occupied by a settler system that is constantly picking, extracting and destroying.

For this butt plug made from coastal materials, we used the miparri (fan palm), which is traditionally used in weaving and medicinal treatment for congestion. Also, the mankarajinga (casuarina pine), which has medicinal uses for skin sores. Nadine was also saying that mankarajinga is a way to find water—if you’re in the bush and you follow the casuarina pine, you will reach water. We also worked with piranga [longbum, a shellfish collected in the mangroves], which is now used as a biometric by scientists when they are measuring what is accumulated in coastal areas. For example, looking for carbon and nitrogen levels near mining sites in sea countries. It was especially used on Rapid Creek near the Darwin military airport to detect PFAS contamination from outdated military fire extinguishers. Longbum is another traditional food, and it can cause diarrhoea through overconsumption, but it’s also now constantly part of scientific surveillance to justify mining companies and military extraction.

Amelia: And then there’s the paperbark butt plug in the shape of a crucifix, which was part of the Mardi Gras float, right? [Paperbark refers to trees in so-called Australia and nearby islands with a pale, papery bark that peels off in thin layers.]

Johnita: Right. Before the missionaries arrived on Tiwi, paperbark, punkaringa, was used to wrap the bodies of the deceased during Sorry Business. But the missionary presence introduces this demand to have coffins instead of paperbark wrappings. A coffin costs three thousand dollars or more, and this is a place where a lot of people don’t have a job. Meanwhile, the settlers don’t even understand how to do burials in this environment: when the wet season comes, you start to see holes everywhere where they have buried their coffins. So back to holes, you know. These are not good holes.

We wanted to talk about the missionary history here because it brings a particular culture of silencing. The religious figures convert people into trusting them as an authority, and then people don’t speak up against all these corporations. When you look at the Tiwi Islanders that Santos is able to bribe in their secret meetings in Darwin Airport, getting them to agree to the Barossa Gas Project deal, you can see they’re all conservative Christians.

So, yeah, all these things are connected, and they’re all part of an ecosystem of leaky holes. And I think that’s my input for the project, but Nadine can talk more about how her community got fucked by all the false promises. And this will happen on Tiwi as well, with the false promise of creating jobs and employing people. Yeah, right, employing who? It’s lies. People here will tell you that after the 2007 Northern Territory Intervention by the Howard government, everything changed. There’s more policing, more racism, more stratification within communities, and so on.

On Tiwi, after the Intervention, they set up Wurrumiyanga and the Office of Township Leasing [Wurrumiyanga is currently the largest community on Tiwi, located at the site of the Catholic Mission on Bathurst Island]. Wurrumiyanga was the first town to sign a lease to the Commonwealth Government for 99 years for, quote-unquote, “economic development.” And you have all these Tiwi Islanders on the front page of the government website who are praising how you can own your own home now; you can achieve the Australian Dream and lalalala . . . But in reality, it’s just control through economic means. If you look at the people on the website, the people in the video, one of them is Ainsley Kerinauia, and she does not own a home. She’s struggling to pay rent to the government while power bills are $50 per week. This is rentier colonialism: you’re just converting people on their own land into paying rent to the illegal government. This is manufacturing poverty. So yeah, there’s a lot going on. We need to care for the land, we need to follow the lead of First Nation elders and so on, but we also need to really look at settler structures and policy.

Amelia: Nadine, are you still there? Can you speak to your own experiences in relation to all of this?

Nadine: Well, with Santos and the big mining boom here, house prices went up ridiculously. So we are living in manufactured scarcity. We had the Northern Land Council, and we were supposed to be consulted, but of course, they rushed the consultations and forced us into this royalty agreement. For all the billions of dollars of gas they have now shipped out from Larrakia Country and all the billions they get in government subsidies, I’ve only ever received about $490 Australian dollars. And then when the gas starts running out, INPEX [another oil and gas company] comes in and says, “Oh, we’ll get the last few years of gas out of this.” And then, all of a sudden, we can’t get any royalties at all because the agreement was with Santos, not with INPEX. So we need a new agreement, and so on.

My grandmother was taken away as a child as part of the Stolen Generation. She was terribly sexually abused in the Missions, and so that has an epigenetic effect on me. We lost a lot of our culture through her experience; she was just so ashamed to be Aboriginal because of the way they were all treated. But she is someone who could now be a bridge between the government and the people here. Instead, it’s some white worker up from Sydney who has only stayed in the community for one year. We are fighting these non-Indigenous white gatekeepers at the top of these organisations and statutory bodies, and they just do everything in their power to get young, budding, beautiful, determined Indigenous people blocked, because they are old, crusty white cunts—sorry, my language. But I mean, I’m thinking of a neighbour of mine. He would sit down on Country and tell you all these beautiful stories and share knowledge, and I remember giving him boxes of food because he would feed all the kids when they were hungry. But now he can’t because he has to rent a house, and for two days he’s had no lights on, because the power got cut. He’s got no money. This man doesn’t drink. He used to run around the island, he was a footy player, and he loved basketball, and he’s fit and he’s healthy. They could have employed him as the local health officer, but no, it’s some white fella who has come in, and his home is a total rubbish tip, but they give the job to him instead of someone in the community.

Doing art with Yangamni and going to the biennale and meeting people like you, we can hopefully get to people’s hearts and spirituality. I also work in creative arts therapy. We dance and sing, and we do art, and that is part of our healing. We know how to heal ourselves; we come from a very sophisticated, very advanced culture, which is the oldest in the world. And we lived symbolically. We never ran out of food. Everything was set up like our own supermarket. You knew where to go and get kangaroo. You put your little fish traps in the water and just flick them out and you got fish. It’s like, it wasn’t a hard thing. It was just so abundant. There was, of course, fighting and jealousy, matters of the heart, but everything was set in place, and it worked.

There are ways we can live on this earth without ripping giant friggin’ holes in the ground. We mob, we lived with a symbiotic relationship with Mother Earth, and with neighbouring tribes, and stuff like that. Because things are connected. They’re going to start drilling thousands of kilometres out there in the sea. We can’t see it, and so they just do it. And, heaven forbid, if there was a disaster, it affects Tiwi and Larrakia and Kimberly mob and everyone because it’s all connected. So we are fighting for everyone.

It’s not one mining project; it’s multiple projects that people need to protest against. Especially in the central desert, the fracking there. I would say that’s the worst because all the aquifers of the so-called Northern Territory are connected—once they pump the chemicals, it will affect absolutely everyone. And, I mean, there goes the billion-dollar tourism industry that they love to pump all this money into—yeah, no worries. Like, crazy, crazy people, they want to fuck up all the things they promote for profit, all the waterways, all the beautiful things. And we are just sitting here like, “Have you mob got split personalities or what?”

Johnita: The last Labor government mining minister [Nicole Manison] now has a job here with the giant US gas fracking company Tamboran: the politician-to-lobbyist pipeline. I mean, you don’t even have to say corruption; it’s just one structure of settler colonialism.

Nadine: We really have to decolonise the mind of Australia, and the hearts of Australia, yeah. Our people are very resilient, very sharing, caring, and patient. But, like Crystal said, when the elders go, we lose that little bit more, each time a little bit more. Yeah, because we don’t practice enough with fucking social media and the TikTok shit. The young ones are obsessed with it, and we just want to bring back culture and ceremony, real life, to people. The memory. Yeah. Hopefully, we’ll be able to achieve that. We will be able to achieve it, we will.

Amelia: Thank you for speaking with me today. I had wanted to ask Crystal about her Evil Ass dream, but since she got cut off and we’ve already been on the phone for more than 90 minutes at this point, maybe I can just add the text about the dream that you published online with the video, and that can be the end of the interview.

Auntie Crystal Love, recorded in an early-arrived Tiyari (Tiwi season of hotness and humidity):

“It was a dream about the gas plantation (Barossa Offshore Gas Pipeline) and mythical creature of Evil Ass Ring with spirit coming right through the asshole. When it talks, bad gas comes from the ring hole of its mouth. Mouth like a bum hole, created by evil and greed. This gas gets passed through the belly, out the ass of one human who passed it onto the next. This is how Evil Ass dreaming infects our people both mentally and physically. It digs a hole through Murntankala. This hole is superstitious—it is man-made and spirit-made at the same time. Murntankala would have helped us but we went against her and Evil Ass got in the middle. Murntankala let Evil Ass do his thing and black people got selfish and let the devil in. Its evil spirit attracts our soul, making us evil. It corrupted the white people first and then it corrupted the black people. The compromised black people let this happen to Murntankala. It’s up to black people to reverse that and think of the consequences—the ones that got too hungry for that mining money. The spirit of Murntankala made the Tiwi and we used the country against her will. Everything happens in a cycle. She gave us and she will take away. She wants us to fight for what’s right.”

Yangamini (“holes” in Tiwi) is a guerrilla collective initiated in 2022 by Tiwi-Warlpiri Sistagirl elder Crystal Love Johnson Kerinauia, consisting of trans and non-binary First Nations and allied communities. The collective accommodates First Nations sexual minorities who seek refuge from the rigid gender customs of mainland communities. Yangamini strengthens gender-fluid bush knowledge and challenges missionary sexual oppression, rentier violence, racialised governance, economic control, rhetorical sustainability, and mining extractions in the settler Northern Territory of so-called Australia. Current members include Crystal Love, Francis Jules Kapijiyi Orsto, Ainsley Kerinauia, Romana Paulson, Joachim Tipiloura, Nadine Purranika Lee and Jens ‘Johnita’ Cheung, with connections across Tiwi, Gulumirrgin, Warlpiri, Kunwinjku, Yolŋu, Wardaman, Karajarri, Gurindji, Burarra, Minjunbal, Bundjalung, Mununjali, and other extracted lands and seas.

Amelia Groom is a writer whose work has often been concerned with time: its undercurrents, its blockages and trickling detours, and the possibilities for its re-routing. Groom’s book Beverly Buchanan: Marsh Ruins (2021) was published in the Afterall One Work series. She has also published essays on topics including mud; Mariah Carey and the refusal of linear time; Scheherazade and “oblique parrhesia”; rust (co-authored with M. Ty); and the role of cats in the art and antifascist activism of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Groom was a tutor and mentor for MFA students at the Sandberg Instituut from 2014 and 2024, and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry in Berlin from 2018 to 2020, as part of the “environs” research focus. They are currently a Visiting Assistant Professor in Feminist Studies at the University of Califiornia Santa Cruz.

- Crystal Johnson, “Napanangka: The True Power of Being Proud,” in Colouring the Rainbow: Blak Queer and Trans Perspectives – Life Stories and Essays by First Nations People of Australia, ed. Dino Hodge (South Australia: Wakefield Press, 2015), 28. ↩︎

- Break Down, Or: Dismantling the House that Narrative Built – Moosje Moti Goosen

- notes towards an otherwise – gervaise alexis savvias

- A Young Cowboy First Saw the Lights: Part 1 – Philip Coyne

- Open Glossary for Queer (immaterial) Architectures – die Blaue Distanz

- BLACK HOLES MATTER! – Yangamini

- Queer and Anti-Colonial Gardening: A Syllabus – M. Ty

- Plot(ting): Practices of Ambiguity — Patricia de Vries

- Cartas de Agua – Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás

- “Raised on Foundations of Slime” – Amelia Groom

- For a Possibility of Care, Not Ownership – Mariana Balvanera