Field Recordings – Liza Prins

This text accompanies the first in a series of mixtapes that arise from an interest in European pre-industrial work-song cultures. For the past three years, my artistic collaborator Marie Ilse Bourlanges and I have participated as stewards in The Linen Project, a collective effort in which we tend to a flax field in Arnhem and explore the possibility of manufacturing linen responsibly and locally with pre-industrial tools. Immersed in the embodied rhythms of flax processing, we began to daydream about the historical songs that supported this work in times past. We dug up Dutch archival recordings at Meertens Instituut, Amsterdam, a research library dedicated to the documentation of language and oral cultures in the Netherlands, as well as French recordings at Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, which houses extensive audio collections. I also scoured digital archives holding collections compiled by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax and his father, John A. Lomax. I listened to many hours of reinterpreted material and dissected several songs in singing lessons.

Through these processes, I noticed an interlingual discourse beginning to appear wherein remarkably similar themes and concepts had been rendering work songs on the fields as aids for the pace of production and, at times, as tools for social organisation, hatching political awareness and dissent. Observing the coalescence of these two distinct phenomena fuelled the questions guiding the mixtape series. The aim is to unravel when and how singing in rural labour practices in Europe transmuted into tools for political consciousness-raising. The series explores the subversive, proto-feminist narratives and voices of working people in pre-industrial songs. Can these voices “unsettle” the historical narrative on which a dominant European identity was built? The series also asks if it would be possible to harness the social functions of these songs at a time when climate catastrophe and the limited political imagination of late capitalism have seemingly checkmated society. Is there a way to reconnect to aspects of pre-industrial singing practices, and what material can people use to build such cross-historical connections?

*

In “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” novelist and dramatist Sylvia Wynter describes how European intellectuals of the Renaissance, in an attempt to secularise the “descriptive statement of the human,” replaced a hierarchical worldview rooted in Christian dogma with one based on race.1 The model of the pious man who went about his days with the ultimate goal of redemption in the afterlife morphed into one in which the rational, white subject—loyal no longer merely to God but to the state and had a political vocation in life—was centralised. This model was not a mere suggestion for a good life, rather, it was rendered by the west as the ontological description of man that othered all alternative modes of living and being human—which is why Wynter speaks of its “overrepresentation.”2 Wynter says: “The Color Line was now projected as the new ‘space of Otherness’ principle of Nonhomogeneity.”3

The Color Line was, of course, not conceived overnight. Not all peoples living on or traversing European soils at that time readily subscribe to or identify with the new description of man, if they were not already excluded based on any perceived non-normative demeanours. Poet, essayist, and translator Lisa Robertson, while summoning writer and poet Édouard Glissant in her Anemones: a Simone Weil Project (2021), declares that “the heretical, mystical strains of thought that had flourished within a heterodox Europe were . . . separated out from the official thought systems precisely in order to be expunged from Europe’s self-representation,” and that the “crusade against the Cathars, constitute the beginning of the political construction of the defensive concept of a bordered, exclusive, rationalist and racialised Europe, and also the start of European colonial destruction of local cultures, languages and peoples.”4

While fully acknowledging the structural violence of colonial difference and recognising how race would come to be, in Wynter’s words, “the most efficient instrument of social domination,”5 I want to add that man’s overrepresentation also required repression of subjects and practices within Europe and that, accordingly, the subversive singing practices at times unsettled it. This is not to negate the fact that racial difference and the colonial heritage of Europe have engendered asymmetrical distributions of power and wealth, yielding privileges for white individuals and worldviews. Still, it is to say that the fabricated descriptive statement of man asserting dominance through mostly empty promises of upward mobility to the white working class harnesses its power by tearing down any forms of solidarity that could have existed between the harshly and horrifically exploited at some point in time. I hate that it has done so with success.6 Further in this text, the use of the term “bawdy” by western ethnographers will stand as an example of the parallel othering processes that Black and white cultural practices were subjected to. For now, I want to say that although a nuanced examination of historical interrelations between racial and class dynamics needs a lot more elaboration than this essay and mixtape offer, I hope they can be a step in the right direction.

Regarding Wynter’s descriptive statement of man, I want to differentiate between the political subject of Renaissance Europe and the working, singing subject that gains political awareness in emergent sociability and through the senses. As a practice-based research project, Field Recordings aims to explore how latent political potential was present any time people sang together while working. This simmering social structure, which might boil over any moment, forms a political dimension that, paradoxically, was entirely neutralised by Europe’s individualist political subject. Turning up the heat under its pot again will help any project that wishes to dismantle the racialised and alienated state of humans.

*

In their book Rhythms of Labour: Music at Work in Britain (2013), scholars Michael Pickering, Emma Robertson, and Marek Korczynski outline how pre-industrial British work songs—mostly in the context of pre-industrial textile work—functioned as social tools in three distinctive ways. Firstly, singing was both created by and helped to support the rhythm of manual labour. Secondly, singing was a way of escaping the draining reality of arduous work. Thirdly, the collaborative effort of singing created a sense of community. Local gossip was often introduced in songs, and workers in the early textile industry found a collective voice through singing and working together.7

Song is a tool that can help to dissipate information about love, work, hope, the price of butter, desperation—economic or otherwise—and politics.

The Belgium Flemish writer Stijn Streuvels aptly describes this dimension of song in a chapter of his popular 1907 novel De Vlaschaard (The Flaxfield), which chronicles a day in the life of a working girl. The novel’s protagonist Schellebelle is 15 and has “a face like the sun, and a head of corn-blond hair, wide and weathered, under which her eyes [gleam] like carbuncles.”8 The large eyes of this adorable protagonist glisten even brighter when, one day, she abandons milking her cows to work with the other women in the flax field. Off to the field she goes, where the presence of the farmer’s son, Luis, makes her feel a tingling sensation. She has noticed it before. It makes her want him to never leave. When he does, not three minutes go by before the girls and women start to sing. Schellebelle is surprised that their song almost entirely drowns out her wish for Luis to return. Gossip and stories about men, seduction, love, and deception are held within what the women sing; racy lyrics are intercut with an occasional cautionary tale. Schellebelle’s ecstatic listening colours her cheeks a fiery red; each song offers a new vocabulary for her budding crush, and the feelings “in her little heart” begin to make sense.9

It’s a compelling image: women of different ages working together in the field, sharing their life experiences through song. The younger women learn from the older ones about love’s wonders while being warned of its deceptions. I want to think that they created, through song, a space for sharing lifesaving information—and Streuvels’s narration can undoubtedly lend itself to a reading that focuses on the collective, somatic practice of singing as a practice of feminist consciousness-raising, whether he intended to do so or not.

There is, however, one considerable problem: Streuvels might not be the trustworthy narrator that his naturalist writing style suggests. He researched and deeply appreciated the life of workers and farmers, yet he also allowed his work to be adapted for the film Wenn die Sonne wieder scheint (When the sun shines again)—a German production that premiered in Berlin in 1943.10 Questions about the trustworthiness and political instrumentalisation of historic materials crop up everywhere when you delve into the histories of rural Europe. At the same time, if we simply avoid looking at these histories, the risk is that we allow them to be entirely co-opted by the political right, without a fight, without at least an attempt to look at rural European histories and traditions through a materialist, feminist lens and find in the heap of conflicted material the traces from which one can build current disruptive frameworks.

The lore of history is skewed and it always has been, which is why this mixtape series will not attempt to idealise or reconstruct the past precisely as it was. Instead, the series will look determinedly at the past as a prelude to the present and seek precedents in those threads that can spin productive fibres for current moments of assembly, awareness, and resistance so that the body’s senses can become theoreticians once more.

As part of oral histories, songs can transform through multiple social contexts and functions, moving from love songs into songs of protest, from work songs into anti-war songs and back into lullabies. My mother used to sing “Bella ciao” (circa late nineteenth century) to comfort or lull me to sleep when I was a child. This song originates in the late 1800s with mondina labourers who sang about the unforgiving working conditions in Northern Italy’s rice paddy fields. “Bella ciao” was later adapted into one of the most potent anthems against fascism in the 1940s when the Partisans sang it in resistance to the occupying forces of Nazi Germany. It also appeared in the TV series La Casa de Papel (2017–2021) and is still an often-heard chant at contemporary protests—against oil, the genocide of Gaza by the hand of the Israeli state, unaffordable housing, etc. The genealogy of songs like “Bella ciao” demonstrates that historical struggle forms a continuum and that the latent political potential of a song can be tapped into at any moment—any moment!11

On the other hand, “La Marseillaise,” originally the rallying cry of the French Revolution, now, as France’s national anthem, instead serves to bolsters the country’s nationalism. This, as well as my mother singing “Bella ciao” as a lullaby, shows that the radical potential of song is never safe from pacifying or corrupting forces. A racy or plaintive love song and the social dimension it evokes may be the harbinger of a political revolt, but the content and form of this message might also be essentialised or subdued in lamentable ways. Hoping to build towards a future that bolsters and learns with the first process rather than the second, the Field Recordings series follows a structure that starts with traditional love songs (Desire, Desire, a Bawdy Escape), then moves to songs emerging from the rhythms of work (Rhythms of Labour), and eventually morphs into protest songs (Songs of Dissent).

The mixtapes in the series are made in the full confidence that people have always and everywhere rejected their marginalised positions and that they have always and everywhere had a political imagination at least as developed as those of their peers and contemporaries.12 For centuries, people have been escaping into (songs full of) love and desire to forget about a demanding workday; this escapism has also contained or mutated into (songs of) active dissent.

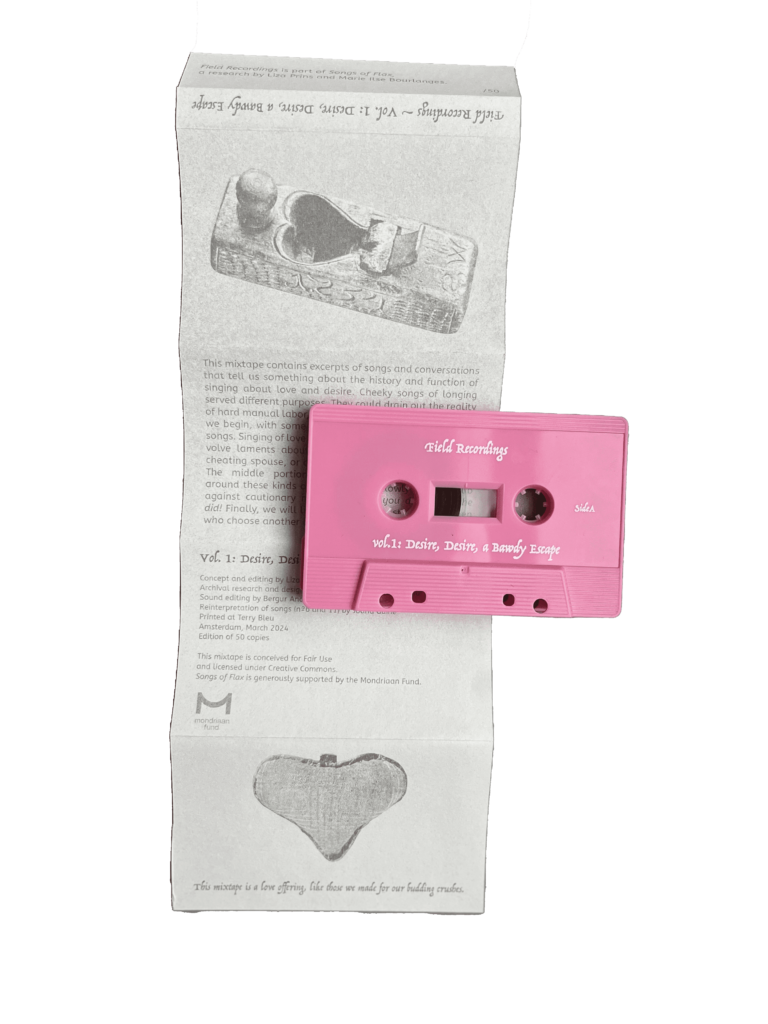

This mixtape is a love offering, like those we used to make for our budding crushes.

Volume 1: Desire, Desire, a Bawdy Escape

This cassette contains 16 excerpts of work songs and conversations that tell stories about the history and function of singing about love and desire. In the context of work, cheeky songs of longing served multiple purposes. They could drain out the reality of hard manual labour, and this is where our mixtape begins, with some historical bawdies. Interestingly, and returning to Sylvia Wynter, songs and rituals in Jamaican folk culture were often described by that exact term: “bawdy.” According to Wynter, Jamaican and African diaspora fertility rites and songs were misunderstood only as saucy and dirty pastimes when they involved, among other things, “the reaffirming of ties with the . . . community and the earth.”13 Although the bawdies here are not ritualistic per se, they can similarly be interpreted as reaffirming the social, political, and natural connections that Industrialism sought to suppress. In doing so, they unsettle the Renaissance individualist interpretation of man and his political vocation. Singing of love could, besides being bawdy, also involve laments about a soured love, a cheating spouse, or an unrequited desire. The middle portion of this mixtape will revolve around these kinds of songs, which often begin to rub against cautionary messages in the style of “Don’t you do what I did!” Finally, there are songs and stories of women who choose lives that were not confined by romantic love.

Here is a short description of the excerpts I hope you will listen to:

1. Interview between Betsy Whyte and Peter Cooke

Betsy Whyte, a Scottish (Romani) traveller, singer, and virtuoso of traditional Scottish storytelling, speaks about the bawdies she would sing on the fields. British ethnomusicologist Peter Cooke is interviewing her. The fragment is cut short, but the transcript of the interview shows that Cooke’s next question was: “What is it about a blue song, a ‘baddie,’ that makes people so cheery?” Betsy replies: “Ah, I don’ know. I don’ know. But it disnae have tae be a baddie, ye ken. No.”

2. “J’ai perdu ma culotte à lui faire l’amour” sung by Germaine Burgaud, Yvette Barreteau, and Fernande Vannier, recorded by Jean-Pierre Bertrand, Gilbert Biron, Nathalie Andre, and Pierre-Marie Dugue

A girl, a shepherdess, lying in a fern bush; another shepherdess who comes to make love without wearing any underwear; and an enigmatic woollen chastity belt are brought up without warning in this French bawdy.

3. “The little ball of yarn,” sung by Elizabeth Steward, recorded by Peter Cooke and Akiko Takamatsu

This is a typical bawdy seduction song recorded in Scotland in 1987. In it, winding a ball of yarn becomes a metaphor for female pleasure.

4. “Moeder ‘k ben zo raar van binnen,” sung by ‘t Kliekske

A girl sings of her youthful desires. Shortly after, her mother warns her not to marry too young. She says: “Three times six is much too soon / Three times seven, that’s young enough / Three times eight, that can still go / Three times nine will stand / But I know for sure / That three times ten is still the best.”

5. “As he walked down by the river/False true love,” sung by Isla Cameron, recorded by Alan Lomax

A bawdy that tells the story of a young girl who is seduced, taken to a man’s bed, and then rejected. In the last stanza, a plant called rue is briefly mentioned: “There’s a herb that grows in my flowers’ garden / Some they call it rue / The fish may swim and the birds may fly but a man can never be true.”

Rue can cause uterine contractions and bring about abortion. Does the reference suggest the girl is pregnant? The song’s vocabulary is rather saucy, but it undoubtedly serves as a warning. Women disseminated knowledge about abortifacient herbs through this song’s lyrics, undermining the power that men held over women’s wombs. Seen in this light, the song could be interpreted as undermining Wynter’s descriptive statement of man.

6. “My Bonny Boy,” sung by Anne Briggs

W. Percy Merrick recorded “My Bonny Boy” or “Many a Night’s Rest” on 17 June 1901 from Henry Hills of Sussex, who learned the song from his mother. Anne Briggs sang her version of the passionate song of a betrayed lover for her 1964 LP The Hazards of Love. This mixtape is an ode to Briggs’s record, and with this song, we have assuredly moved into the love-sick and cautionary phase of our listening session.

7. “De spinster,” sung by Joana Guiné

This is a Dutch song first recorded in 1853, in which a woman recounts being seduced—or assaulted—while spinning yarn. She does not utter a word to the brown-eyed man, but her constantly fraying thread must have shown her anxiety and could very well signify the loss of her virginity. There are numerous versions of the song in Dutch and German; in all versions, her thread breaks and she loses her ability to spin.

In one particularly grim version of the song, the last stanza echoes: “With seriousness I rejected the youngster / this seemed to make him even stouter / impetuously he flew around my neck / and kissed my jaw red like fire / Oh! Tell me, sisters! Tell me, if it were possible / that in the end I spun still further?”

8. “La fileuse,” sung by Camille Renouard, recorded by Hubert Pernot

Another, this time French, account of a spinster who is seduced by a shepherd. The singer keeps on repeating the lines: “How could you / How could you / How could you think I’m spinning (or: running away) / We can’t always spin away (or: run away).”

The French word for spinning, filer, has a double meaning, so one is never entirely sure if the singer cannot continue to spin or if something or someone is hindering her capacity to run away. Later in the song, it’s learned that the shepherd’s love is sincere and that the priest gives the singer a blessing to continue the kissing. If he wasn’t a priest, she would have made him her lover, too—this is a song full of mixed messages.

9. Interview between Mary Gillies and Alan Lomax

In 1951, Alan Lomax collected stories and songs from lobsterman Neil Gillies and his sister Mary Gillies, who was acting as Lomax’s hostess in the Scottish island of Barra. Mary discusses her mother’s wool work and the song she used to sing while at work. She says: “She was a nice-looking woman and a lovely singer. And I have still got some of her songs . . . and I'm not . . . the only thing I am sorry for is I didn’t . . . learn them . . . better than what I did.”

10. “’S chunna mise mo leannan” (I Saw My Love), sung by Mary Gillies, recorded by Alan Lomax

Mary Gillies continues to sing one of her mother’s songs, a Gaelic song. It heralds the lamenting voices of this mixtape as it tells of a lover who does not recognize the singer.

11. “Cantiga da ceifa,” sung by Catarina Chitas recorded by Michel Giacometti and Joana Guiné

This poetic Portuguese lament and work song is a warning about the wink of a boy’s eyes and the warm sun while harvesting. The first stanza says: “From above the bread is harvested / Oh, under below stays the stubble / Girl don’t fall in love / Oh, with the boy that winks his eye.”

12. “Er was een meisje van achttien jaren,” sung by Gretha Sok, recorded by Will D. Scheepers

A deceptively cheery song that takes a turn and lands on femicide. A man seduces a girl. After he leaves her “with a deep guilt,” he takes her into the forest and, in the final stanza, tells her: “your final resting place is here.”

13. “De valse liefde heeft zovele zinnen,” sung by Anna van der Biezen-Akkermans recorded by Ate Doornbosch

Based on an arch that includes a seduction, a fall out of favour, and a murder in the woods, this song appears to be a more developed version of the previous one. It laments the death of a pregnant girl named Dina, who is killed by the man who had claimed to be in love with her: Mr. Volto. Dina’s class position is one of the reasons that Mr. Volto’s friends encourage him to get rid of her.“Volto, thou dost shame thy tail / That thou shouldst let thy lust err on a maid.” He acts on their advice.

14. “En bij de prille vroege morgenstond,” sung by Trees Torfs, recorded by Pol Heyns

We finally arrive at the mixtape’s more agential female section. In this likely Dutch song, a hunter encounters a beautiful shepherdess, but she rejects him because she “prefers her liberty.” This version was recorded in 1938.

15. Interview and song by Eudoxie Blanc, recording/interview by Pierre Bonte

Eudoxie recounts how her husband would never let her sing while spinning. Now that he is dead, she does as she pleases. Here is a little excerpt of the interview Pierre Bonte did with her in 1977:

PB: “Are you a widow, Eudoxie?

EB: What do you mean?

PB: (louder) Are you a widow?!

EB: Oh yes, since six years ago. Oh, and as I said, that’s when I felt resuscitated because my husband didn’t like it.

PB: He didn't like what?

EB: Well, he didn’t like me spinning. He didn’t like me laughing too much with people. I shouldn’t sing . . . So I spent my youth . . . Not that I liked that . . . And now, voila! I’ve got very nice grandchildren, and we’re all happy, too, so things are going well!

PB: Are you happier now?

EB: Oh ha, no comparison.”

16. “The false true love,” sung by Eliza Pace, recorded by Alan Lomax and Elizabeth Lyttleton

This song is a (very) different version of the fifth song we listened to. In this iteration, sung by Eliza Pace in 1937, it is not entirely clear which lover confronts which about their infidelity. On Shirley Collins’s record False True Lovers (1959), she and Alan Lomax note:

The False True Love is one of hundreds of examples showing that the British folk song tradition has grown steadily more lyrical in the past two or three hundred years. As the role of the ballad singer lost its importance, the narrative pieces were broken down into fragmentary lyric songs . . . The original piece is a tragic ballad called Young Hunting, probably Scots in origin, but widespread throughout Britain and North America. It tells of a young man who rides by to visit an old sweetheart. When she bids him to lie down and spend the night, he says he prefers his new light of love. Whereupon the jealous girl stabs him, throws his corpse into the well and curses him. The remainder of the ballad consists of a dialogue between the murderess and her little parrot, the sole witness, who insists he will tell all and will not be bribed or threatened into silence.14

liza prins is an artist, researcher, and writer based in Amsterdam. Her work focuses on feminized and pre-industrial labor, as well as the material and immaterial conditions and tools for social organization that emerge from it. Using collaborative performative methods touching on re-enactment techniques and improvisation, she seeks to re-establish a connection with material histories and social imaginations.Prins studied fine art at Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and she has a master’s degree in artistic research from the University of Amsterdam, where her thesis investigated the intersections of feminist, new materialist methodology and performative practices.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (fall 2003). ↩︎

- Ibid., 282. ↩︎

- Ibid., 316. ↩︎

- Lisa Robertson, Anemones: A Simone Weil Project (Amsterdam: If I Can’t Dance, 2021), 14–15. ↩︎

- Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” 262. ↩︎

- Wynter writes of a similar regret when she describes how the American bourgeoisie, before the 1960s, mitigated class conflict by encouraging a white working class to see themselves as having access to the opulence of the dominant middle class, even though they were “not selected by Evolution in class terms [but] by the fact of their having all been selected by Evolution in terms of race.” Ibid., 323. ↩︎

- Marek Korczynski, Michael Pickering and Emma Robertson. Rhythms of Labour: Music at Work in Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↩︎

- Stijn Streuvels. De Vlaschaard (Amsterdam: L.J., 1907). ↩︎

- Ibid.: 101 ↩︎

- Ine van Linthout and Roel vande Winkel. De Vlaschaard 1943: Een Vlaams boek in nazi-Duitsland en een Duitse film in bezet België. (Groeninghe, Kortrijk/Brussel, 2007). ↩︎

- This is a small introduction to the research on “Bella ciao” that my collaborator, Marta Pagliuca Pelacani, and I will undertake at a later stage. ↩︎

- I am taking this insight from David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (New York: Picador, 2023). ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, 108, unpublished manuscript, no date, housed in The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, https://monoskop.org/images/6/69/Wynter_Sylvia_Black_Metamorphosis_New_Natives_in_a_New_World_1970s.pdf. ↩︎

- Shirley Collins. False True Lovers (Folkway: 1960, LP) ↩︎

- Open Glossary for Queer (immaterial) Architectures– die Blaue Distanz

- SELL YOUR FART! BUTT PLUGS AGAINST GAS DRILLING! -Amelia Groom

- Queer and Anti-Colonial Gardening: A Syllabus — M. Ty

- Plot(ting): Practices of Ambiguity — Patricia de Vries

- Cartas de Agua – Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás

- “Raised on Foundations of Slime” – Amelia Groom

- For a Possibility of Care, Not Ownership – Mariana Balvanera

- Field Recordings – Liza Prins

- Heartbrake – Giulia Damiani

- Plot, Tree and Lane – Hanneke Stuit & Neeltje ten Westenend