Break Down, Or: Dismantling the House that Narrative Built – Moosje Moti Goosen

Today is Saturday, 26 October, 2024 (or, a beginning)

I am writing from a hospital room where I am being treated with a methylprednisolone (MPS) IV cure for symptoms of acute donor organ rejection. I had a bilateral lung transplant in 2017. Earlier this year, I was in intensive care at the same hospital, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam. I was here from the beginning of January until the end of March, after having contracted Covid-19 while on immunosuppressive medication for my transplant lungs. The first two weeks of January I was in an induced coma. The current acute organ rejection, I am told, can be cured, although a similar treatment earlier this year did not yield the expected results.

Quoting the late Palestinian-American academic and activist Edward Said: “a beginning is a first step in the intentional production of meaning and the production of difference from preexisting conditions.” I, on the other hand, will or must begin by moving away from my intentions.1 I had intended to write a text according to the preexisting conditions of the academic or scholarly tradition: the argumentative essay.

a first step

on the other hand

But this, this seemingly matter-of-fact movement towards the beginning—beginning to write—ends up not being the place to start from, in my case, because my body and, therefore, my mind, is also always somewhere else. (See the above).

Said, repeated:

“. . . the intentional production of meaning . . .”

“. . . the production of difference from preexisting conditions.”

I was trained in academic writing, the kind of writing that knows what it is going to say, adding something of significance to what has already been said. Academics write the facts, supported by arguments. For me, in order to maintain this kind of writing, I have to force myself to change my mind, suppress the facts of life.

The thing is, no matter how much learning and reading and writing I do, or, more accurately, because of it, I never arrive at a clear beginning with confidence (real or falsified) of mind, knowing what I’m going to say, making a solid argument, singular and uncontested. My thoughts are never solid or resolved. I don’t know how to begin; I do not arrive at conclusions.

I am a living breathing problem because scholars provide disembodied discursive expertise on subjects. Subjectivity is out of the question. I am a living breathing problem to writing because authors, in post-structuralist, academic terms, are considered to be dead.

And yet, here I am, writing. And with my decision to write, a thought begins to form—always, inevitably. Maybe it’s a dream image, like those conjured in automatic writing sessions by the surrealists. Maybe it’s a recurring idea. Maybe the thought is so premature it is hardly worth one’s attention. I like to linger in this state of mind: observing something on the brink of existing, something not-yet-known and about-to-be.

A prompt from Oblique Strategies, a card set for creative processes by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, first published in 1975, says: “Once the search is in progress, something will be found.” It means, I think, that the search creates the object of recognition, it projects an outcome, somewhere in the future. Even when you don’t know what you are after, something will always make itself seen and known, because perception and expression are close cousins or maybe even twins. At least they are born of the same body. They produce, if not a structure or a pattern, a motion

a first step.

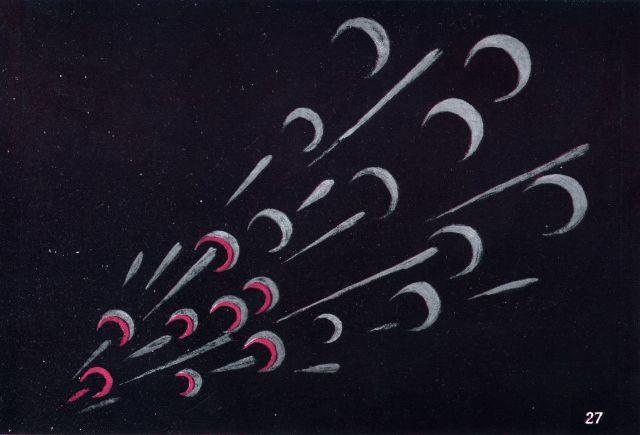

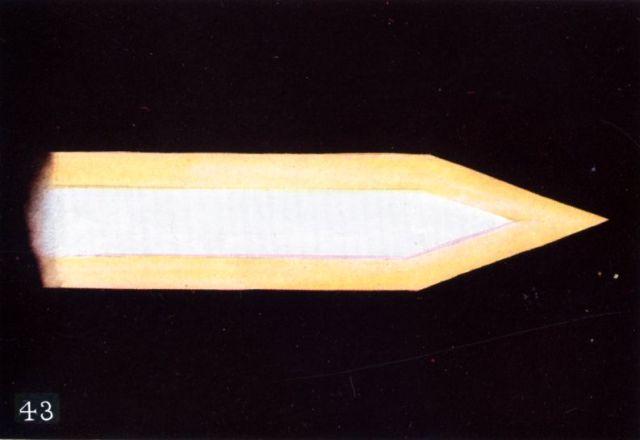

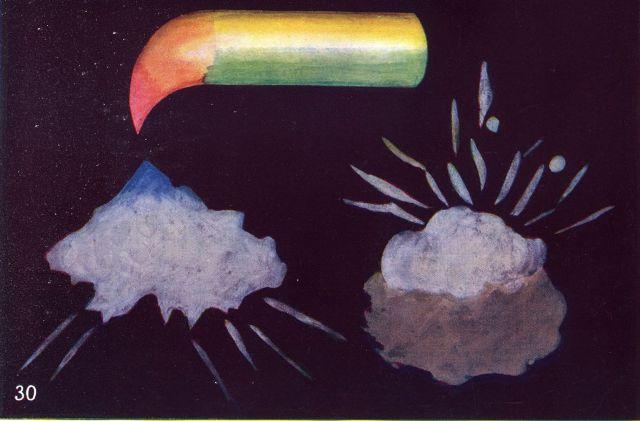

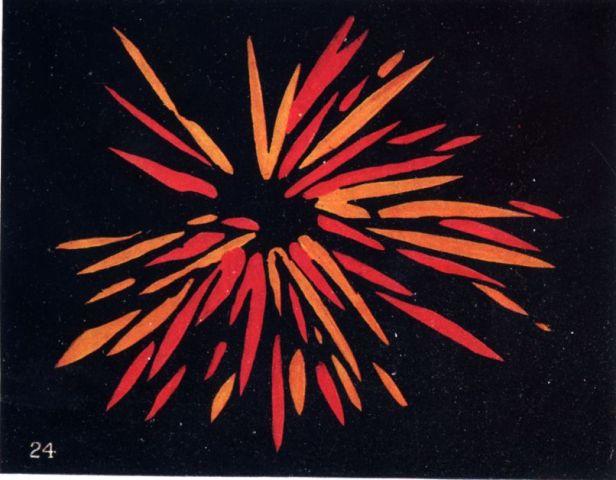

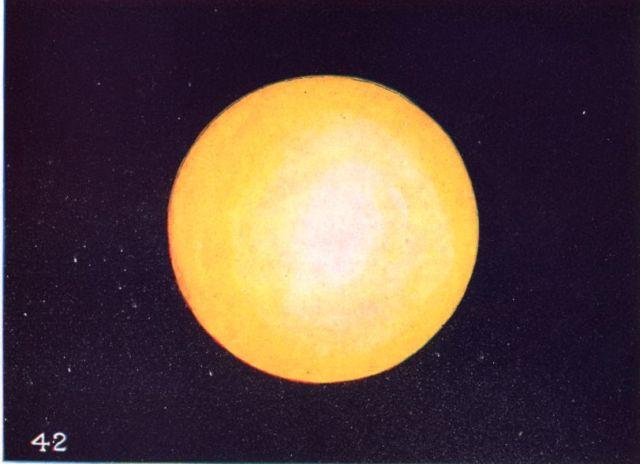

I have a book by theosophists Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater, in which they present a series of thought forms: visual depictions of thoughts based on what the authors call “clairvoyant observations.”2 In 58 illustrations, they show how their thoughts appear to them, what actual form and colour they take in their minds. The thoughts are visual, pure form, made using gouache and watercolour paints. Only the captions reveal something about their content. Some thoughts look like fireworks in an empty, black sky. Others remind me of the abstract figures or blots that sometimes appear on your eyelid before falling asleep, or the visual auras of a migraine attack. The drawings are aesthetically pleasing but they fail to capture what thought does. Thinking is a process, a phenomenal action, always in action: it moves, it is all over the place, it remains unfixed. It is subject to change. Morphing, evolving, mutating, and adapting itself according to new insights, input, experiences, and acquired knowledge. An essential part of thinking is its inevitable, necessary unthinking: we change our minds, and we do it all the time.

What am I thinking? What are my intentions, and what is an academic intention? What does writing do and how do we read the intentions of the writer? These are thoughts and questions forming themselves, right here inside this room, inside a hospital, inside an unreliable body.

(Hold these thoughts for now.)

I’ve decided to follow these inarticulate thoughts-without-an-argument (which is not the same as a thought-without-purpose) by writing. To find out, in my own experience of body and mind, what constitutes a narrative, and in what way narrative gives form to or structures—directs or dictates, perhaps—this pleasing form and motion called thinking. And I’ve decided to do so because I want to be realistic. More than a scholar, I want to be a realist. Because my own beginnings, as a writer, are always corrupted, so to say, by my life’s circumstances—interrupted, for instance, by the reality of a nurse entering this room to unplug the IV line in my right lower arm, so that I can move around the room without the IV pole. I have to stay inside this room because of isolation protocols. That means I am stuck with my thoughts for the next few days.

In 2013 I was diagnosed with a progressive lung disease. It coincided with my intentions: I was about to begin a four-year period of PhD research.

before the first step

on the other hand

Life became its own form, with its own will, encroaching upon my stated intentions, to the extent that I felt as though every piece of writing, every form of thinking (every thought form) from then on would need the pretext of this vital, real-life health condition that intervened in the “preexisting conditions” of a disembodied academic scholarly intention. Illness turns your body into a story that wants to tell itself. You cannot argue with it. And what I learned from writer Susan Sontag is that you can analyse and criticise illness as much as you want, you can throw all the possible arguments towards it, but unfortunately, it doesn’t make you any less sick in the end.

Beginning, therefore, and still not, as Said wrote, with “the production of difference from preexisting conditions.” Beginning, neither “through first advancing some ideal type which it [or I] then seek[s] to fulfill”—that is to say, neither through writing and arguing towards something that has been prefigured, pre-formed, and presupposed. But beginning, from the misstep or even the mishap, and everything that is supposedly beside the point.3 Writing in a hospital bed, from the supposedly besides-the-point lateral position and point of view of a sick woman who is in chronic unstable health. A first step: beginning by stepping out of narrative line.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live . . . We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.4

These famous words by author Joan Didion are often quoted out of context. That’s because we long to live by those words. We want to believe in the stories we tell ourselves. Narrativity, as cultural theorist Mieke Bal points out, is a cultural mode of expression, an almost—almost—natural form of cohering, of making sense of the “shifting phantasmagoria” that comprise our existence.5 But Didion wrote these lines in a state of crisis, caused by the disruption of these storylines. “I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement.”6 She was losing narrative sense: she had admitted herself at the psychiatric clinic at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, where doctors described her condition as an “attack of vertigo and nausea, and a feeling she was going to pass out.”7 Breaking down or breaking up, stories no longer made sense to her and therefore, couldn’t reassure her any longer.

How does incoherence appear to a clairvoyant, to Besant? Didion sees flash pictures, images with no meaning, sequences without plot, the collapse of narrative integrity.

So my first fully formed thought beside the point, here inside this room on the tenth-floor pulmonary unit of a hospital in Rotterdam, is more of a memory-refresher, reminding me of what I already knew, what we all know, I believe, when we quiet down and observe our minds: that the structure of thought is anything but linear or progressive (everyone who has ever had a breakdown knows what it is like to think in circles). This, the thinking itself, is on my mind. And it brings me back to my academic education.

In academic writing we also tell ourselves stories: we bring order to a chaos of existing, sometimes contrasting ideas and meaningless data. We cohere information, add context, in a framework of our choice. All of this, while striving for an order of knowledge. We manipulate data into an order of linear narrative, pretending that thought naturally and progressively leads to order and resolution. Academics are transparent about everything except about the fact that this order is fabricated. My thinking is wild and disorderly and its order in writing is a fiction. The fiction of linearity, singularity, and narrative structure helps us structure our thoughts. I strive for a knowledge that is open and aware of the entanglement between narrative fiction and the production of knowledge.

“One enters a room and history follows; one enters a room and history precedes. History is already seated in the chair in the empty room when one arrives,” the Canadian poet and thinker Dionne Brand writes.8 This is another way of saying that there are writers who cannot begin at what is generally conceived as “the beginning” of a narrative; writers who cannot assume the role of the impartial scholar, and cannot detach themselves from lived experience, as is favoured by rationalism. Rationalism, of course, is another story we tell ourselves. A very dominant story. One enters the story of an empty room where history resides, but only hauntingly, without making itself “known” (or present)—pretending it is not there. The room itself is already a construction.

I, too, am constructing this writing, fragment by fragment—I will not pretend that writing is a natural expression. The thought, any thought here, is formed by the consideration of a word (and not another), a sentence, a syntax. The text is the thought form. The thinking doesn’t “happen” in the supposed room; the room (the writing, and its form) is a fundamental part of the thinking.

My room has:

a hospital bed

a shower

air conditioning

medical equipment

an IV pole

a television to pass the time

a clock to see time passing

a window view

a door that has to stay closed

To pass the hours inside this hospital room, I brought books of poetry by Etel Adnan, JJJJJerome Ellis, and Anne Boyer; I brought the script of Blue, Derek Jarman’s film about his experience of illness and AIDS. None of these texts are told in a linear fashion. It’s almost as if intuitively, or perhaps instinctively, I knew when packing my bag that prose was not going to help me through these days.

Yesterday, in fact, I did not read at all, as I was caught up in the routines of hospital care: intake, medication, tests, preparation, waiting, receiving, exchanging information. I listened to podcasts instead—recent episodes of Between the Covers with writers Dionne Brand, Adania Shibli, and Isabella Hammad. I felt better and less lonely hearing these women talk to each other, inside this sanitized room. They also entered my mind, forming thoughts, so to say, because all three of them express, in one way or another, their concerns with what the podcast host David Naimon calls language’s misuse: “the deliberate misuse of language as an enabling of an ongoing genocide.”

Elephant in the room: there is a genocide going on, killing Palestinian men, women, and children, destroying their houses, depriving them of water, food, gas, electricity, health services and medicine, under the pretence of war.

Intermission. Room NE1013, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam. Voices in the Room

Isabella: “Palestinians were always denied the ability to narrate for themselves . . .”

Wislawa (Szymborska), quoted by Isabella: “I prefer the absurdity of writing poems to the absurdity of not writing poems . . .”

Robyn Creswell, quoted by the host, David: “While readers may be tempted to look for political messages, Edward Said suggests that the real drama in Palestine’s body of literature is the writers’ struggle to come up with a coherent form, a narrative that might overcome the almost metaphysical impossibility of representing the present . . .”

In my notebook, I ask myself: Who has the ability, and who has the power, the right to imagine something coherent out of the experience of the present?

Adania: “Palestine is an ethical relationship. That is to say, how the word Palestine, erased from the map, is no longer related to a nation-state or to a country or specific group of people but is open to so many possibilities, meanings, and practices . . . It transforms what is being erased into something that cannot be erased any longer . . .”

Dionne: “. . . narrative must take a more open form than the handed-down processes of the narrative of imperialism and imperialistic structure . . .”

Adania: “. . . writing begins with a refusal to explain to people who narrate too well . . .”

Dionne: “. . . there’s a regime of literary practice that demands, from certain bodies, explanations for their presence. And this is the indignity of it. This is the insult (…) It’s an economy of some kind. But that economy dovetails with colonialism and imperialism. And therefore it demands of these bodies a certain explanation about their presence …”

Dionne: “Capital summons certain parts of our being that are useful to it.”

Another note in my notebook, told by Adania:

“In Arabic, the word for literature and ethics is the same.”

David: “To put forward a grand narrative of Palestine, given the absences, would be to put forward a fiction.”

David’s words remind me of something I read in Sylvia Wynter’s short essay, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” a piece of writing that I have been reading and re-reading, in the context of the research group Art & Spatial Praxis focused on “plotting,” organised by Patricia de Vries, lector at Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam. In the essay, Wynter quotes the Guatemalan writer Miguel Angel Asturias who said, after the CIA-backed coup of the legally elected government in Guatemala in 1954: “These things that happen? . . . It’s best to call them fiction!”

With the essay, Wynter, who began her academic career researching Caribbean literature, culture, and the history of slavery, proposes what could be considered an ethics of fiction. That is to say, she looks at the way fiction and the novel have been instrumental in the telling of a story based on humanism, rationalism, Christianism, and the violent de- or sub-humanising of beings in Europe’s project of colonialism and imperialism. From the same essay: “History . . . these things that happen, is, in the plantation context, itself a fiction; a fiction written, dominated, controlled by forces external to itself.9 Wynter deconstructs history, and more particularly the history of humanity itself, as a fiction, a narrative genre.

We tell ourselves stories, we create fictions, in order to rule and reap profits. Humanity, as it is “told” by the west, pretends omniscience, universalism: an absolute point of view that in itself is purely fictional. Universal man is a fiction (or, a genre, in Wynter’s words) produced by a narrative founded on the silence, the ontological existential silence of the subhuman, the Black slave, who has no power to produce his own narrative, who has no “room of his own.”

Invoking Brand here, in my room: One enters a story and the plantation follows, one enters a room and the plantation precedes. Or, the totalising force of the plantation is the empty room; the empty room is the plantation. The plantation is the foundation. And the story, the history, the science or academic knowledge that does not take this into account before all else is always already a fiction.

The entanglement between fiction and history goes both ways. The western novel in its popular form, as a product of entertainment for readers of different classes, was established in the seventeenth century and evolved alongside global disruptive changes of imperialism, colonialism, and the Atlantic slave trade. In “Novel and History,” Wynter, quoting philosopher and sociologist Lucien Goldmann, writes: the novel form “appears to us to be in effect, the transposition on the literary plane, of the daily life within an individualist society, born of production for the market.”10 In a decolonial reading of the British novel of this time, stories of the daily lives of individuals making up British society are haunted by slavery and wealth extracted from the plantation “elsewhere” (a compartmentalised room, sometimes an attic). In most cases, this elsewhere of slavery and extraction is not made part of the story: the wealth of the British individuals “just is.”11

(The story, most of the time, is only half the story.)

Meanwhile, here inside room NE 1013, evening has fallen, and I’ve picked up my small blue copy of Jarman’s Blue (1993). Derek is my loyal friend in illness. He has been for a long time.

Derek: “The worst of the illness”—I actually wrote down “The words of the illness”—“is the uncertainty. I’ve played this scenario back and forth each hour of the day for the last six years.”

Back and forth and back and forth. A compulsive, repetitive non-linear thought form without beginning without end. This is how I will conclude my day.

fig. 51, 52. helpful thoughts (Besant and Leadbeater, Thought Forms, 1905)

Today is Monday, 28 October, 2024 (or, in the middle of inaction)

I have been waiting all morning to be discharged from the hospital. I’m an impatient in-patient eagerly waiting to get out of here. Time is passing, my thoughts linger.

So I may have arrived at the supposed middle of the action, the moment where the narrative is supposed to take a turn; situations are about to unfold and explain themselves; arguments are made, and so on. At this point, the reader is, perhaps instinctively, anticipating a transition, a turn of plot. In a lecture last year, Hammad talked about the plot element known as the turning point, not knowing that one—a point, it seems now, of no return—was about to happen. (It was nine days before the attacks by the Al-Qassim Brigades, the military wing of Hamas, happened, on 7 October, 2023).

Isabella, back in my room: “Somewhere recently humanity seems to have crossed an invisible line, and, on this side, naked power combined with the will to profit threaten to overwhelm the collective interests of our species.”12 It’s been a year of ongoing destruction and murder in Gaza, and yes, we are still in the middle of it.

Isabella: “the flow of history always exceeds the narrative frames we impose on it.”13 In this year, I have learned most about Gaza and Israel from fiction writers, and that is because they don’t make a secret about their writing fiction. This, to me, is more honest and therefore, closer to the truth than the stories told by the media, sold to us as news. The frame in western mainstream news media up until now is that this “war” began with the attacks by Hamas on 7 October, 2023. But from a Palestinian narrative point of view, these attacks took place in medias res, in the middle of the action that was already happening, ongoingly, since the displacement of Palestinians in 1948. The Naqba is ongoing. A flashback to the opening paragraph of Said’s essay, “Permission to Narrate,” from 1984, provides some backstory here and also, a recurring motif: in the essay’s opening lines he refers to a report by an international commission speaking of attempted “ethnocide” and “genocide” by Israel.14

Forty years later, Israel is still in denial, while western authorities are still—again—contesting, negotiating, and suppressing this observation, made then and now.

And back and forth and back and forth and Never Again.

Only yesterday, I was watching a Dutch talk show from my hospital bed, where Dutch Palestinians were interviewed under the host’s conditions that they condemn the Hamas attacks and declare right there on the spot and in front of the rolling cameras that the state of Israel has the right to exist.15 Before the interview could even begin, it had already turned into a rather hostile interrogation, and it was remarkable and disturbing to see narrative power in action, to see what it takes to keep language—to keep people—fixed in place.

One enters a room and one is not allowed to begin at the beginning.

Today is Monday, 13 October, 2025. An after-thought, inserted here.

I want to return to Wynter, whose earlier critical work on the novel as a cultural commodity provided the base for her analyses of the more structural aspects of narrativity and the emergence of the human as Homo narrans:

I identify the Third Event in Fanonian-adapted terms as the origin of the human as a hybrid-auto-instituting-languaging-storytelling species: bios/mythoi. The Third Event is defined by the singularity of the co-evolution of the human brain with—and, unlike those of all the other primates, with it alone—the emergent faculties of language, storytelling.16

That the human is therefore, in part, a human invention by a species that lives by the stories it tells itself, also tells us something about the way humans produce knowledge. In writer Rinaldo Walcott’s words:

Wynter is interested in demonstrating how Europe’s conception of Man ‘overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself.’ Her project, then, comprehensively attends to the ways in which we have come to and produced our contemporary conditions of being human—wherein Man is the measuring stick of normalcy and Man’s human Others are excluded from this category of being—and how we might unsettle and undo this conception of humanness.17

Wynter’s work is a form of intellectual epistemological activism. She suggests no less than a decolonisation of being itself, by imagining a new “form of life”: a “new way of knowing” that is based on what the Martinican poet and thinker Aimé Césaire proposed, in his 1944 piece titled “Poetry and Knowledge” as a new science of the word.18 This hybrid science is based on the notion that understanding human culture, language, and storytelling (the mythoi) is crucial for comprehending the natural world (bios) or sciences.

If the human as a category is an invention, a myth produced by the storytelling human, we can become active readers of the so-called universal knowledges established by four centuries of academic science, tracing back its thought forms, so to speak, to their initiating agents or, narrators. This is what Wynter does, taking up Césaire’s call for a science of the word. “My major proposal is that both the issue of ‘race’ and its classificatory logic (as, in David Duke’s belief that ‘the Negro is an evolutionarily lower level than the Caucasian’) lies in the founding premise, on which our present order of knowledge or episteme [Foucault, 1973] and its rigorously elaborated disciplinary paradigms, are based.” We live by an order of knowledge that is not only Eurocentric in its foundation, but also, more profoundly, an order in which “white racism becomes logical.”19

In “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Wynter defines the plantation as a superstructure that initiates the modern world, which she describes as “the process of the reduction of Man to Labor and of Nature to Land under the impulsion of the market economy” thus providing the basis of our late-capitalist global free-market system.20 In an interview with the journal Small Axe, she extends on this:

I’m going to suggest that the world in which we live today, it is not primarily the mode of production—capitalism—that controls us, although it controls us at the overtly empirical level through the institution of the free market system, and the everyday practices of its economic system. But you see, for these to function, the processes of their functioning must be discursively instituted, regulated and at the same time normalized, legitimated. So what I am going to suggest is that what institutes, regulates, normalizes and legitimates, what then controls us, is instead the economic conception of the human—Man—that is produced by the disciplinary discourses of our now planetary system of academia as the first purely secular and operational public identity in human history.21

The university is also the plantation. The assumed objectivity of the sciences is a fiction, a story it has to perform in order to live.

Back to Monday, 28 October, 2024.

Inside this hospital, I cannot avoid the fact that I am of flesh and blood and bones: nurses check my vitals—temperature, blood pressure, pulse, oxygen saturation—multiple times a day. Each morning I am asked to weigh myself on a scale to prove that gravity still has its effect on my body. So I feel I am physically burdened with the question of what it means to be human and to write academically. The university—its boards, its systems of bureaucracy, its neoliberal rationale—feels more and more like an enemy today, fighting its own students for taking an ethical position, against the fossil industry, against Israel’s genocide in Gaza and the West Bank, against fascism.

So much is so wrong in the very extreme today. Hammad: “our moment, the one in which we now live, feels like one of chronic ‘crisis.’”22 What is the writing form for this chronicity? This moment will extend or repeat itself, as long as we do not look at the root causes that cause conflict and catastrophe to “flare up” time and again, like a chronic disease.

This time asks for a treatment, beyond the “logic” of war and geopolitics. Academics need to come to terms with their foundational story, their “origin myth.” They need to criticise the legacies and effects of the plantation economy and its own historical complicity in the telling of this story on a global scale. Will a turn of plot, within the same academic narrative and narrative structure, suffice? Or do we need to give up this story altogether and re-narrativize our truth? Here, I am not just pointing to the story itself but also, more profoundly, to the way knowledge is represented in traditions of reasoning, argument, objectivity, material reductionism, linear narrative, and so on.

Wynter says, I refuse to live by the story that tells “blacks that they are nothing, not the same as whites.”23 These are the stories that emerge from the rooms in the academy, and we have to face this problem. In her essay, “Moral Inhabitants,” novelist Toni Morrison condemns the kind of academic scholarship that trains students “to make distinctions between the deserving poor and the undeserving poor but not between rice and human beings.”24 What is reasonable or even rational about an education that cultivates this type of disinterest, a kind of learning that requires people to forget their ability to see with their own particular eyes, sense with their unique bodies? Morrison continues, “That is what indices are like, of course. Not the fan-shaped spread of rice bursting from the gunnysack. Not the thunder roll of barrels of turpentine cascading down a plank. And not a seventeen-year-old girl with a tree-shaped scar on her knee – and a name.”25

Yesterday evening, before going to sleep, I read the following words by poet Anne Boyer:

One imagines that one can escape a category by collapsing it, but if one tries to collapse the category, the roof falls on one’s head. There, a person is, then, having not escaped the category but having only changed its architecture. Once it was a category with a roof, now it is a category in which one is buried in the rubble made of what once was a roof over their heads.26

Once again I am with the poet and the fiction writer. I don’t want to go on producing knowledge from inside the academic room that is so obviously in moral ruins.

Before I fell asleep, I saw in my mind this metaphorical rubble, the “rubble” of academia’s self-ruination, by giving narrative consent to Israel’s genocidal project, and by violently suppressing protests by students who demand their universities to break ties with Israeli partners. I also saw in my memory the actual rubble and dust of bombed building structures in Gaza, which I am seeing every day on my Instagram feed and “stories.” These two images, metaphorical and actual, merge, they turn into mirror images. They are no longer discrete forms of thought.

The narrative news frame that supports the violence in Gaza and dehumanises Palestinians is so sickening that I for one feel story-afflicted by it. You do not have to be Palestinian to take this personally. Where, what, and who provides the roof of narrative structure? Does it give shelter, protection from external forces? Protecting, whom? Whose rubble? Who establishes the room where history is already present, seated on a throne? My thoughts move on and over into the rubble of a text, into the breakdown of a narrative, but a breakdown for the sake of health. Wynter: “Every poem says things that you have to break down to explain.”27 Perhaps our story time must come to an end.

I think we need texts whose words are self-conscious and worked-through, demanding our active engagement in thought-forming, so that it is up to us, one human reading body after another, to make up our minds and embody the insights it has helped produce.

Postscript in the Middle, still Monday, 28 October, 2024.

Meanwhile, all the time, I have been waiting for the approval of my discharge from the hospital. Waiting is always endless, a form of enduring. I am now waiting for the medical exams that are to show my health’s improvement after treatment—even though, the doctors admit, it’s probably too early to tell. Still, doctors are required to monitor progress, if only in retrospect. Again: linear structure, a form of fiction.

So this is now being typed (thought-formed) on my phone as I am seated in the waiting room of the hospital’s lung clinic, waiting for someone to measure my lung capacity with a spirometry test. I’m full of thinking, a busy mind, but also extremely tired—it’s so incredibly tiring to wait and to have to keep on waiting. My mind and body are drifting somewhere between these two opposing energetic forces: thinking and waiting. Can you be story-suspicious and still have a desire to write, or are these bound to cause friction together?

I think I would like to think of narrative in positive terms, as something flowing, as a stream of consciousness in which one of the currents will force its way up, while undercurrents do their work more quietly. Yes, I think, I like to think like water, but through words. This is not to say I want to write intuitively or without intention, but rather pushed forward and jammed sideways by all the elements that affect my thinking. And I want to take these affectations seriously. Like the woman who sits beside me, right here and right now, in this waiting room, who makes me self-consciousness about my rapid finger-tapping on my phone. Yes, this is how I would like to think about narrative. But I also observe the persistence of a story of straight canals made to ship units of cargo from A to B.

Today is Thursday, 31 October, 2024 (still somewhere in the middle or, N.H.I: No Humans Involved)

I’m back home, in my living room, making an effort to pick up where I left off. Obviously, this, too, is a fiction and narrative strategy—the passing of time pretending not to have happened.

In 2024, Graywolf Press published its fifteenth-anniversary edition of Zong! by poet M. NourbeSe Philip. It’s a book of poems based on the massacre of over a hundred Africans by the crew of the British slave ship Zong in the days following 29 November 1781. The ship, owned by the Liverpool-based William Gregson syndicate, took part in the Atlantic slave trade. The company had taken out insurance on the lives of the enslaved Africans as cargo, and when the ship ran low on drinking water following navigational mistakes, the crew decided to throw sick and/ or weakened Africans overboard. Relying solely on the public document of the Gregson v. Gilbert court case over the insurance money, Philip’s poems excavate from its legal vocabulary what she calls “the story that cannot be told yet must be told”—the murder of some 130 Africans, drowned in the sea because they were presumed to be worth more in insurance money when sacrificed, so as to preserve the rest of the “cargo.” Quoting from the Gregson v. Gilbert report: “This was an action on a policy of insurance to recover the value of certain slaves.”

Zong! consists of phrases, words, and fragments of words taken from the Gregson v. Gilbert legal text, in verbal collages of increasingly disintegrating language, and interrupted by the occasional word or phrase in languages that, as Philip imagines, were “overheard on board the Zong.”28 This vocabulary is translated in an appendix glossary, comprising words from West African languages such as Shona, Twi, West African Patois, and Yoruba. Dutch words also appear.

For the Dutch-speaking reader, this is where the plantation hits home, inside the room, inside the body. Before the ship Zong was purchased by the William Gregson syndicate, it had sailed in the slave trade under the Dutch flag. It had been baptised “Zorg” by the Middelburgsche Commercie Compagnie, which was in the business of shipping enslaved Africans to the Dutch colony of Suriname. Zorg, in Dutch, means “care.” Zorggg, a word with a guttural sound that is typical of the Dutch language. The sound is formed at the back of the mouth and produced by pressure in the low abdomen, the gut. Not everyone can utter from the gut and pronounce this word properly.

I can.

A Dutch voice—my own—makes itself heard on the page of Philip’s poetry, reverberating, back to myself. Suddenly I am caught up in this, my tongue implicated in Philip’s words. Words that, I realize, also give a sound (a gut, a body) to the silencing of these African men, women, and children.

Zorg. To take care. Uw zorgen wegnemen; to take away your worries; to unburden. Burden: a load, typically a heavy one. Burden, shipload, cargo, care. This ship made its first voyage in 1777, delivering Africans to the Dutch colony of Suriname. Passed on to its successive owner, the company of William Gregson, the ship was painted over. Zorg turned Zong. Care was meaningless to begin with, a perversity in the context of the plantation—nonsense adding further distortion to an already distorted course of history.

Zong zong zong.

Other Dutch words that appear in Zong!

bel: bell

bens: thing

geld is op: money is spent

hand: hand

ik houd van u: I love you

op en neer: up and down

tak: arm

tong: tongue

I am unfamiliar with the word bens, an archaic word. Apparently, it is a thing, but what kind of thing is it? I have to look it up in a Dutch dictionary. More than a thing, I read, it is someone’s thing: someone’s property, owned goods. The economy of a thing. Dutch, it is sometimes said, is an economic language. Not a word too much. But also efficient, pragmatic, straightforward. The Dutch have a koopmansgeest, a mercantile spirit. Always in for business, turning people into business.

Ik ben/ jij bens

(I am/ you thing)

A tak is a tree branch, or the metaphorical arm of a tree, as in a branch of knowledge: een tak van wetenschap. In de wetenschap—in the knowledge—of the Dutch reader. The Dutch reader is in the know. A body, however, does not have two taks or takken: it has arms. The body is not a metaphor. It is made and unmade by language. This misguided speech, this “violent syntax,” as Brand has named it, is the tongue, de Nederlandse tong, of Zong. The tong of Zong is no longer silenced within me; it produces an anti-narrative that can only be told by not telling.

For a Dutch reader to read the history of slavery is to be confronted with the long stretch or arm (de tak) of a historical vocabulary, reaching right into the present moment, onto our present tongues. It is a terminology that turns a human being into a ship’s cargo, a shipload, an insurance’s worth, a unit of labour. In Lose Your Mother (2007), academic and writer Saidiya Hartman lists the terms that were introduced in the terminology of fungibility in the Atlantic slave trade, in order to quantify the body of the negro slave:

The Portuguese referred to them as braços, arms [again, a tak?] or units. The Spanish called them pieza de India, which roughly translates into an ‘Indian piece.’ A pieza was a ‘mercantile unit of human flesh,’ which often comprised more than one human being. A male slave in the prime of his life was the standard against which other slaves were measured. People with limited physical abilities or who were elderly constituted only a fraction of apieza. Two boys or a mother and her child might equal one pieza. The Dutch called them leverbaar, that is, a healthy or deliverable male or female slave.29

I am back home but still sick and therefore not capable of working full-time (full disclosure: I am writing this in my pyjamas, half-reclining on the couch). Wynter enters my mind again. She tells about the Rodney King beating by the L.A. police and how, in the university—she taught at USCD—this brought students together:

And then, on the radio we heard that whenever the police were told that somebody was calling about the trouble in their household, and the people were black—or if they were white prostitutes—they would say ‘NHI’: no humans involved (…) I then wrote an open letter to my colleagues, ‘No Humans Involved.’ In a sense, meaning that all knowledge should be addressed to that concept.30

Much of her comprehensive theories on the genre of the human, “the coloniality of being,” and the present-day overrepresentation of Man2, with the jobless poor as outside but establishing the sanctified social order, emanate from this letter (to which her colleagues never responded).

The letter is her beginning towards the production of difference from preexisting conditions, but it cannot take off in a place where this call for change is ignored.

I, too, am affected by the categories imposed on me by governing authorities. The Dutch UWV, Het Uitvoeringsinstituut Werknemersverzekeringen or Employee Insurance Agency, in charge of national social security and welfare, evaluates the health condition of its citizens and judges whether and to what extent, he or she is benutbaar—“usable” for employment, employable. Benutbaar, leverbaar. In a capitalist society, one must deliver. In order to function and participate in society, you have to use your takken, you have to carry out labour. I know there is no human involved when my employability is calculated in FTEs, full-time equivalents. In the past, I have been labelled as GBM—geen benutbare mogelijkheden. Deepl translates this to “no exploitable possibilities,” un-exploitable. This is the language of the Dutch verzorgingsstaat or welfare state, a state taking “care” of its citizens. Zorrrrgg.

(Elsewhere, I read that a seaman is still referred to as an AB today: an “able-bodied.” And if you’re not able-bodied you are thrown into the sea).

Let me be clear: I am not likening the fate of enslaved human beings to that of the sick or disabled. As it turns out, slavery and sickness are not allowed to go together. A slave cannot be onbenutbaar. It has to be leverbaar at all costs. When, for want of water, ill health turns to slave, slave is off-loaded, thrown overboard as cargo, damaged goods. “Sixty negroes died for want of water . . . and forty others . . . through thirst and frenzy . . . threw themselves into the sea and were drowned; and the master and mariners . . . were obliged to throw overboard 150 other negroes,” Philip quotes from the Gregson v. Gilbert case.31 We know and only know about the fate of these drowned African men, women, and children, because their bodies serve as extras in a case that considers not their illness nor their drowning but the legal effects of this.

Sylvia:

Most of all, and this is the point of my letter to you, why should the classifying acronym N.H.I. [No Humans Involved], with its reflex anti-Black male behaviour-prescriptions, have been so actively held and deployed by the judicial officers of Los Angeles, and therefore by ‘the brightest and the best’ graduates of both the professional and non-professional schools of the university system of the United States? By those whom we ourselves have educated?32

Implicated in the Gregson v. Gilbert case, the report of the ship’s owners v. the insurance company, is the story of all those humans involved who cannot tell their stories and whose stories cannot be told. Their case was never the case.

And there are always stories that remain untold, by the telling of other stories all the time. A CNN news item from a week ago reports the suicide of an Israeli soldier with PTSD after having been deployed to Gaza and tasked “with driving a D-9 bulldozer, a 62-ton armoured vehicle that can withstand bullets and explosives.” The news item informs that soldiers like him had to “run over terrorists, dead and alive, in the hundreds.” Reading this news item, I’ve learned more about the bulldozer than about the hundreds of Palestinian bodies who were not involved, because they were never considered human beings to begin with, because they were always already labelled as Hamas terrorists or Hamas supporters. And we know about these run-over corpses—one quoted soldier refers to these dead human bodies as “meat”—only because they figure as hauntings, spectres, in the flashbacks of traumatised Israeli soldiers, not because they matter in and of themselves. “He got out of Gaza, but Gaza did not get out of him,” the mother of the dead Israeli soldier is quoted saying.33 These are the stories that are legitimated—stories that do not just side with a particular point of view but that require the other, the Palestinian, to be subhuman. To cite Said again, “The Palestinian narrative has never been officially admitted to Israeli history, except as that of ‘non-Jews’, whose inert presence in Palestine was”—is—“a nuisance to be ignored or expelled.”34

If these are the stories in which oppressed bodies (drowned bodies, run-over bodies, undeliverable bodies sick for want of water, bodies entering the room where history is already seated) are consigned to perform the script of their own dehumanisation; stories in which “Palestinians are expected to participate in the dismantling of their own history,” would it still mean something if they—or we, on behalf of the people in Gaza—seize permission to narrate, as Said hoped for, forty years ago, or are we now past that point?35 Is this a turning point?

From the relative peace and quiet of my living room, I end this day, this Dutch October evening, with a spiritual plea by Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott, a poetic answer.

“Pray for a life without plot, a day without narrative.”36

Today is Friday, 8 November, 2024 (still stuck in the middle).

This morning, I had an appointment at the lung clinic to perform another spirometry test. My lung capacity shows a slight decrease. My doctor thinks it’s too minimal to take action, but the change is too significant for me to pretend as if nothing is happening. I fall back into a state of worrying limbo. This, too, is part of chronic illness. After what has turned into almost a year of unstable, uncertain health, how to keep faith? What to do with the back and forth and back again, on and on, the back and forth to the hospital, the medical protocols, the adjustments of treatment and all the medication, the verdicts of test results?

I have turned on my TV and watch some of the evening news programs. There was a riot yesterday, and there are different sides of the story. Supporters of the Israeli football club Maccabi Tel Aviv came to Amsterdam, where, after the match, and after public provocations (racist anti-Arab chanting on the streets and in the metro, an attempt at vandalising a taxi, and the removal of a large Palestinian flag from a residential building), they were sought out by Amsterdam youth and assaulted in violent attacks. Reporters and politicians, including the Israeli president Isaac Herzog, all too eagerly jump onto the storyline of a present-day “pogrom” by Dutch-Moroccan teenagers on scooters and fat-bikes. The word works magically, like a spell—of course it does: it excludes, expels, and it morally overrules all other possible readings of the events. On TV I watch people express their disgust of these young male’s behaviour, condemning their hideous actions, calling for “speedy trial” so their deviance will be re-affirmed judicially and they can be put to jail. Everyone speaks about them, but it occurs to no one to simply ask them: Why? What happened?

Why? And why not? In her letter to her colleagues, Wynter refers to an editorial in The New York Times, which points out “that it costs $25,000 a year ‘to keep a kid in prison; which is more than the Job Corps or college.’ However, for society at large to choose the latter option in place of the former would mean that the ‘kids’ in question could no longer be perceived in N.H.I terms as they are now perceived by all. 37 Why not try something different for a change?

Five months later (or: could today be the end of something ongoing?)

Thoughts keep forming, appearing, disappearing, and reappearing. What becomes part of a text, and what remains untold, or is overlooked, forgotten? What is made insignificant? Time moves on. Here’s a note I took from poet Etel Adnan’s Shifting the Silence (2020), one of the books that was with me in that hospital room, when I started writing this text, five months ago:

We also think in ways we’re not aware of. That sounds like a paradox, or nonsense, but I’m serious. I experienced double thinking: one thought sliding on another, I was startled, didn’t know which one to follow, lost sight of both. I was also slightly scared: are thoughts bouncing balls? Do we really own them?38

I wrote (and am writing) this text in a diaristic form, with jumps in time. The diary imposes a chronology which is different from the constructed linearity of a story. In the flow of time, from the midst of life, we do not know what is going to happen, what the future looks like, if and how it all ends. Instead of prefiguring an outcome, the diary traces an unfolding, it performs a not-knowing, a not-yet, which becomes readable in retrospect. The diary does not require the coherence or logic of a linear narrative, which would require me to edit out what mattered in the moment, but what has been absorbed or dissolved in the meantime, by the continuity and constructed coherence of a time passing. What to say? Mid-January I lost my father-in-law; he fell into a coma and died after a major stroke. What also happened, around the same time: Israel and Hamas agreed on a ceasefire, which came into effect on 19 January 2025. It was broken again by the Israeli forces on 18 March. Netanyahu said that the army’s renewed actions were, in fact, “only the beginning.” So we are back at the beginning, apparently. Again: who decides what constitutes a beginning; who can begin and end things, at their mercy? Who can put people that have other versions of the story under “administrative detention,” their humanness put on indefinite hold? Does it still matter, I wonder, to point at the past glimmers of hope, however small—the ceasefire, Palestinians gathering around long tables amid the rubble of former homes, breaking communal iftar on the first evening of Ramadan; displaced people returning to their homes (or what remains of them), finding, perhaps, a photo or other remnant of their former lives; family members, separated by the war, by checkpoints, finally reuniting? Does it matter to tell this, when this hope is crushed again by fire, a deliberate blockage of food, water, electricity, medicine, and the killing of humanitarian workers trying to save lives? What remains to be told? What remains of the telling itself?

Linear narrative asks, beforehand, what matters in hindsight, what is to be lifted from the flow of time. But we live and we think and we feel right here, and always now.

Dionne Brand, in A Map to the Door of No Return:

“I had come here in search of a thought.”39

Like Brand I want to write, not in order to tell stories, but in search of a thought. Language initiates these searches, form-ulations. The writing itself becomes the thought-form. Over the last months, we (a small group of readers) have come together on a monthly basis to discuss what “the plot” means in Wynter’s thinking, and what “plotting” could do to counter the order of knowledge that produced and produces the overrepresentation of Man (Man1, Man2). The plot is first and foremost a place, the peripheral piece of land assigned to enslaved plantation workers to grow their own food for their own subsistence. This in order to maximise the profits of the plantation. (So that they can take care of themselves and the plantation owners do not have to deal with their needs as human beings.) Wynter writes: “Around the growing of yam, of food for survival he [the African peasant transplanted to the plantation in the Caribbean] created on the plot a folk culture—the basis of a social order.”40 This order literally emerged from the same grounds as the plantation, but was also an alternative to its system of profit, extraction, and exploitation, yielding cultural forms of survival beyond the sustenance of food, such as Vodou and, later, the blues. As the percussionist, visual artist, and herbologist Milford Graves says in an article by Melvin Gibbs: “Black music in this country [US], during the time of slavery . . . it was music that played an integral part of their survival. The music was not used to get out and impress some music critics . . . It was out there to save your soul, to heal you.”41 The plot is therefore more than the land itself, it is a place to live, sustain life: to survive, regardless, in spite of, the plantation order of economy and extraction.

But plotting, to plot, is also a verb. Plotting may refer to a scheming or planning in secret: the clandestine organisation of a subversive action, resistance, or rebellion. On the plot, the enslaved workers plotted revolts and escapes. The plot is a site of potential, a place to imagine things differently. In a conversation with Black studies graduate students, Wynter cites Langston Hughes: “The land that has never been yet—And yet must be.” And she proceeds, “That’s the land you’re going to fight for. You see? The land that’s not been yet.”[1] That is also the plot. Wynter’s work can be seen as an ongoing effort in, and call for plotting difference, on the epistemic grounds of academia.

Lastly, the plot is a narrative device, a matter of story, and a means to make stories matter: an ordering of events into a meaningful structure, which also requires an act of imagination. The difference between story and plot is perhaps most effectively exemplified by author E.M. Forster in Aspects of the Novel (1927):

Let us define a plot. We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. “The king died and then the queen died,” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief” is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. (…) Consider the death of the queen. If it is in a story we say ‘and then?’ If it is in a plot we ask ‘why?’42

Why, again, why? And perhaps we also need to ask ourselves what is outside of the question put forward here—why do we grieve the death of some and not those of others? Why the king and the queen and why not the child that is starving to death in a hospital that is under siege? Why is the hospital that I am returning to, back and forth and without much linear progress, a place of assumed care and safety, whereas in Gaza, hospitalised patients are always already at risk of dying—if not of ill health, then by Israeli fire? Why are these questions out of the question?

I want to live by the questions I ask myself. I cannot do this by pretending I have answers, conclusions, resolutions. I had come here in search of a thought and have ended up writing my way out of the academic form.

A woman in a hospital gown leaves her belongings behind, sweeping the dust of rubble from her sleeves. As she walks from the ruins of her former shelter, she is no longer writing towards the solidity of its architecture but in refusal of it. Proposal for a new story: collapsing the narrative plot into a plot of land that is open to other forms of thinking. This thinking, this thought form, begins by imagining something else on this plot, or even better: it lets vegetation take hold and lets the weeds grow their own course.

(Today is 19 October, 2025, and it is unending)

“But thinking (alas) does not happen in front of your eyes, with a clear horizon.

It spreads its light.”

—Rosmarie Waldrop, from the poem Asymmetry in The Nick of Time.

This text was written in dialogue with the other members of the research and reading group on Plotting: Patricia de Vries (organiser), Laura Dubourjal (coordinator), Gervaise Alexis Savvias, Tabea Nixdorff, and Philip Coyne, as well as with various episodes of Between the Covers. This podcast, by writer David Naimon, has been a space (a plot?) that nurtured my hope, provided insight, and sustained my belief in the need for ongoing resistance, against the hideous realities and fictions of the present moment. Transcripts of the interviews that have informed this text and/or have been cited from can be found here:

- BTC Interview with Dionne Brand on Salvage. Reading from the Wreck: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/dionne-brand-between-the-covers-interview/

- BTC / Jewish Currents Live: Dionne Brand & Adania Shibli in Conversation https://tinhouse.com/transcript/jewish-currents-live-dionne-brand-adania-shibli-conversation/

- BTC Interview with Isabella Hammad on Recognizing the Stranger: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/115699/

- BTC Interview with Isabella Hammad on Enter Ghost: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-isabella-hammad-interview/

- BTC Interview with Dionne Brand on her poetry: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-dionne-brand-interview/

- BTC Interview with Adania Shibli on Minor Detail: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-adania-shibli-interview/

Moosje M Goosen

I am a writer and researcher living and working in Rotterdam. Since 2013, when I was diagnosed with a progressive lung disease that eventually led to a bilateral lung transplant in 2017, my relation to work has changed. With the ongoing care for my body and donor lungs, and a post-transplant, unpredictable health condition always drawing me back to what matters here and now, I have become more ambivalent towards defining myself in terms of work. Writing and reading are my daily practices and I do them both with and without the idea of “work” on my mind. Writing is my response to the raw texture and fabric of life. It is my primary way of thinking—whether analytically or in more experimental forms of prose and poetry. I consider what I do to be most productive between disciplines; between literature and art; between genres of writing; between discourses and between academic and artistic research. Most generally speaking, I am interested in the many forms and lives of language: the “spark of being” (Mary Shelley, Frankenstein) animated by writing.

- I was guided towards this beginning that refuses to be a beginning by the lecture of British-Palestinian writer Isabella Hammad who, in her Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture presented at Harvard University in September 2023, began with a reference to Edward Said’s Beginnings (1975). Hammad’s lecture is published as Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative (London: Fern Press, 2024). ↩︎

- Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater Thought Forms (New York: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1905). Also accessible online at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16269/16269-h/16269-h.htm. ↩︎

- Edward Said, Beginnings. Intention and Method (New York: Basic Books, 1975), 4. ↩︎

- Joan Didion, “The White Album” in The White Album (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979), 11. ↩︎

- See: Mieke Bal, Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, Fourth Edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017). ↩︎

- Didion, “The White Album,” 13. ↩︎

- Ibid., 14. ↩︎

- Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001), 25. ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Savacou 5 (June 1971), 95. ↩︎

- Ibid., 97. ↩︎

- Referring here to Mr. Rochester’s wife, Bertha Mason, the “mad” Creole woman in the attic, in Charlotte Brönte’s Jane Eyre (1847). ↩︎

- Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger, 75. ↩︎

- Ibid., 3. ↩︎

- “As a direct consequence of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon an international commission of six jurists headed by Sean MacBride undertook a mission to investigate reported Israeli violations of international law during the invasion. The commission’s conclusions were published in Israel in Lebanon by a British publisher: it is reasonably clear that no publisher could or ever will be found for the book in the US. Anyone inclined to doubt the Israeli claim that ‘purity of arms’ dictated the military campaign will find support for that doubt in the report, even to the extent of finding Israel also guilty of attempted ‘ethnocide’ and ‘genocide’ of the Palestinian people (two members of the commission demurred at that particular conclusion, but accepted all the others). The findings are horrifying—and almost as much because they are forgotten or routinely denied in press reports as because they occurred. The commission says that Israel was indeed guilty of acts of aggression contrary to international law; it made use of forbidden weapons and methods; it deliberately, indiscriminately and recklessly bombed civilian targets—‘for example, schools, hospitals and other non-military targets’; it systematically bombed towns, cities, villages and refugee camps; it deported, dispersed and ill-treated civilian populations; it had no really valid reasons ‘under international law for its invasion of Lebanon, for the manner in which it conducted hostilities, or for its actions as an occupying force’; it was directly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacres.” Edward Said, “Permission to Narrate,” London Review of Books 6, no. 3 (16 February 1984). Also accessible online: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v06/n03/edward-said/permission-to-narrate. ↩︎

- And why? Why the need all over the media for people to affirm this? I’ve added this footnote at a later date to emphasise the absurdity of this question: On 5 November, 2025, Francesca Albanese, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories, was asked by a reporter whether she believed that Israel has the right to exist. Her answer: “Israel does exist! Israel is a recognized member of the United Nations. Besides this, there is not such a thing in international law like the right of a state to exist. Does Italy have a right to exist: Italy exists! . . . What is enshrined in the law is the right of a people to exist.” ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations, in Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. Katherine McKittrick (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 25. ↩︎

- Rinaldo Walcott, “Genres of Human. Multiculturalism, Cosmo-Politics, and the Caribbean Basin,” in Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, 190. ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter, Joshua Bennett, and Jarvis R. Givens, ““A Greater Truth than Any Other Truth You Know”: A Conversation with Professor Sylvia Wynter on Origin Stories,” Souls 22, no. 1, (2020), 123–137. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wynter, “Plot and Plantation,” 99. ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter cited in David Scott, “The Re-Enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter,” Small Axe, no. 8 (September, 2000), 159–160. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger, xx. ↩︎

- Wynter, Bennett, and Givens, “A Greater Truth than Any Other Truth You Know,” 126. ↩︎

- Toni Morrison, “Moral Inhabitants,” in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2019), 43. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Anne Boyer, Garments Against Women (London: Penguin, 2019), 59. ↩︎

- Wynter, Bennett, and Givens, “A Greater Truth than Any Other Truth You Know,” 132. ↩︎

- M. NourbeSe Philip, Zong (Toronto: The Mercury Press, 2008), 196. ↩︎

- Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, (repr. 2021; London: Serpent’s Tail, 2007), 68–69. ↩︎

- Wynter, Bennett, and Givens, “A Greater Truth than Any Other Truth You Know,” 129. ↩︎

- NourbeSe M Philip, Zong! (2008, repr.; London: Silver Press, 2020), 189. ↩︎

- Sylvia Wynter, “‘No Humans Involved:’ An Open Letter to My Colleagues,” Forum N.H.I. Knowledge for the 21st Century 1, no. 1 (Fall 1994), 43. ↩︎

- Nadeen Ebrahim and Mike Schwartz, “‘He got out of Gaza, but Gaza did not get out of him’: Israeli soldiers returning from war struggle with trauma and suicide,” CNN (21 October, 2024), https://edition.cnn.com/2024/10/21/middleeast/gaza-war-israeli-soldiers-ptsd-suicide-intl/index.html. ↩︎

- Said, “Permission to Narrate.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Cited in Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return, 42. ↩︎

- Wynter, “No Humans Involved,” 46. ↩︎

- Etel Adnan, Shifting the Silence (New York: Nightboat Books, 2020), xx ↩︎

- Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return, 157. ↩︎

- Wynter, “Plot and Plantation,” 99. ↩︎

- Milford Graves cited in Melvin Gibbs, “Making Contact” in Milford Graves: A Mind-Body Deal. Mark Christman, Celeste DiNucci, and Anthony Elms, eds. (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2022). ↩︎

- Wynter, “The Greater Truth,” 129. ↩︎

- Field Recordings- Liza Prins

- Break Down, Or: Dismantling the House that Narrative Built – Moosje Moti Goosen

- notes towards an otherwise – gervaise alexis savvias

- A Young Cowboy First Saw the Lights: Part 1 – Philip Coyne

- Open Glossary for Queer (immaterial) Architectures – die Blaue Distanz

- BLACK HOLES MATTER! – Yangamini

- Queer and Anti-Colonial Gardening: A Syllabus – M. Ty

- Plot(ting): Practices of Ambiguity — Patricia de Vries

- Cartas de Agua – Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattás

- “Raised on Foundations of Slime” – Amelia Groom