Cartas de Agua – Francisca Khamis & Maia Gattas

Maia Gattás and Francisca Khamis Giacoman met in the West Bank in 2019, where Francisca was conducting a residency in Birzeit and Maia was traveling to film scenes for her documentary Viento del este (2023). In this publication, they commit to a letter exchange, wherein they aim to engage in a dialogue that addresses various memories surrounding water in the territory of occupied Palestine.

To carry out this initiative, they draw from heterogeneous archives linked to this territory: historical documents; excerpts from films, such as Port of Memory (2009) by Kamal Aljafari, and The Salt of This Sea (2008) by Annemarie Jacir); personal archives, which encompass memories of their families in diaspora in the form of letters, photographs, and oral history narratives, among others; and their own records from their travels through Palestine.

They propose to establish a correspondence format that facilitates a process of visual and textual exchange. In this approach, correspondence is not only conceived as an archival technique but also as a tool for engaging in active dialogue with the personal archive, enriched by interaction with memory, exchange with the other, and connection with other sources.

Letter 1: The Movies

25 January, 2024, Bariloche, Argentina

My friend,

I haven’t seen you since 2019. I have a memory that on the day of our farewell in Al-Manara Square in Ramallah, you made me taste a new fruit. I don’t remember its name, it was pink and prickly on the outside and white and soft on the inside. You were doing a residency in Birzeit, working with your great aunt Labibe’s stories. I think I still have a file with her voice on some external disk from that time.

I also remember going together to the Dead Sea, hitchhiking our way there. I think we hesitated for a long time figuring out whether that piece of beach we went to was a Palestinian or an Israeli area. The images and sounds I filmed that afternoon are today at the end of Viento del este, my film. There I say: “Palestine has three seas: the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, and the Dead Sea.” In a previous version of the voice-over I said: “had three seas” instead of “has,” but it seemed more in line with my political position to be able to say that they still belong to it.

When I screened my film in London in October, a girl in the audience told me that this ending was in tune with the song that is currently being sung in Gaza demonstrations around the world: “From the river to the sea Palestine will be free,” a phrase that has caused so much controversy and censorship. Here, in Argentina, we don’t sing that in the marches for Palestine, so I didn’t know it, but I was very happy to know that my documentary- which was the result of many years of work and was released in 2023 – echoed with the present.

The first movie I saw about Palestine was in or around 2012; its name is The Salt of this Sea. At that time I knew nothing about the country of my ancestors, and I went to see the movie looking for information. Everything was confusing and cryptic to me. I remember that Soraya, the main character, wanted to reach the sea and for that she had to enter Israel illegally with Emad, her Palestinian friend. Annemarie Jacir, the film’s director, generously gave me a fragment of her film to become a part of mine. It is the scene in which Soraya enters the waters of the Mediterranean, in the area of Jaffa, the city where her grandparents’ house used to be. She swims in the sea but at the same time cannot enjoy it because she is angry.

Years later, at a documentary festival in Buenos Aires, I met the Palestinian filmmaker Kamal Aljafari. In his film Port of Memory (2010) there also appears a desire and nostalgia for lost water. He also filmed in Jaffa, a place that became a symbol of dispossession and exile for Palestinians.

Aljafari takes a fragment from the Israeli musical Kazablan (1974), where the song Yesh Makom (There is a place), performed by Yehoran Ga ‘om, appears. In that scene the protagonist finds himself trapped between the images of the sea of the past and that of the present. The form of temporal palimpsest always seemed to me to be the fairest way to experience time—perhaps because I read too much Walter Benjamin! When I met him, Aljafari told me something that I treasure and that I will never forget: he told me that he often went to the shore of the Mediterranean Sea to collect debris and tiles from the Palestinian houses demolished by the state of Israel. He liked to keep those remains, those fragmentary material memories that the tidal movements brought back.

From Maia

Letter 2: To See the Sea

22 January, 2024, Concón, Chile

Good morning, good afternoon, good evening. Because I don’t know at what time of day you’ll read this. Time passes, but what makes sense of humanity remains the same.

That’s how John Berger begins his reading of Letter from Gaza (1956) by Ghassan Kanafani.1

I started writing you this letter sitting in front of the sea in Concón. I’ve always wanted the sea to be part of my landscape, but unfortunately, I was born and raised in Santiago. And the truth is, I’m not aware of when was the first time I saw the sea. How do you feel about something you’ve never seen? A conch shell in your ear to imagine together what we could never touch.

All this water in front of me and behind me are the wildfires that don’t stop growing. I am thinking about the power of water. A stream of water falls from the ravine next to the building, the only space where they can’t build. That stream of water prevents real-estate companies from destroying that land; that same stream of water could right now be preventing all those houses from burning in Valparaíso.

I think of water as the archive, as that stream that passes and changes the territory for those who come to inhabit it afterwards.

It’s been five years since we met in Palestine, where I arrived eleven years ago for the first time, driven by those stories I heard so much about a territory that didn’t feel like I belonged to. My first trip was guided mainly by two photos: The first one, where my relatives appear sitting at what seems to be a lunch in the field, in Al Makhrour. The second, a photo of my grandfather standing on the wall in Haifa next to another person, facing one of Palestine’s three seas.

The first time I went to Palestine was in 2014. I crossed through Jordan where I spent about eight hours waiting to be allowed to cross. They asked me everything, in every possible way. At first with some patience and in the end with quite some violence. That’s when they recognized me as Palestinian and when for the first time I felt I belonged there.

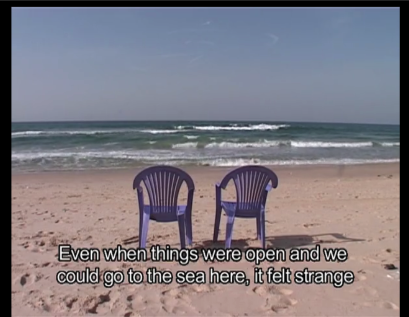

I haven’t seen Salt of This Sea, but your story about Soraya makes me think of María, during my stay in Beit Jala at my relatives’ house. I didn’t know them before, but they welcomed me as one of their own daughters. They set up a bed for me next to María’s, my younger cousin. At that time she was 18 and had never seen the sea. When I arrived, she told me she had been waiting for a few months for her permit to cross. After a week, the permit arrived, so we planned a trip to Tel Aviv. We crossed by bus, arrived at the station with a first mission: to buy a swimsuit for María. I came with the radical idea of not leaving a single penny there, but life is different when it actually happens. We found a place at the station, she picked out a couple of swimsuits and went into the fitting room. Then the salesman asked me where I was from and I said Chile and my cousin said Colombia—where part of her family lives today. After a few minutes of silence, I couldn’t help but say, “But we’re also Palestinians.” His expression changed and he started shouting at us saying he would shoot Palestinians. We grabbed our things and ran out of there.

We went to the beach without swimsuits, and this first visit to the sea with a bitter taste made me understand that life in diaspora forms an identity that doesn’t always fit with those who still live there. Experiencing the sounds of the sea from a conch shell doesn’t always make you understand the dangers of the swells.

Returning to Kanafani, the phrase he sends so emphatically to Mustafa in Letter from Gaza turns me around: “No, I’ll stay here, and I won’t ever leave.”

Maia querida, after reading your letter, I kept thinking about the palimpsest and just yesterday a friend shared a quote from Susan Sontag that made me remember you: “Time exists in order that everything doesn’t happen all at once… and space exists so that everything doesn’t happen to you.”

There are many things left for me to say, more streams of water for the next letters.

Sending you a hug, amiga

Francisca

Letter 3: The Union of Rivers

8 February, 2024, Bariloche, Argentina

From one fire to another fire,

from one river to another river.

Here in Patagonia, where I live for part of the year, every summer there are new fires, many of them intentional. A couple of weeks ago I lost the view I have from my windows because of the smoke brought by the wind—I lost my sight, but the forest lost thousands of acres!

A few days before that I had shown you through video call the mountain I see from my desk, but that day nothing was visible anymore. The horizon was gone, the breadth to which I have become accustomed. That night I had trouble sleeping. It was as if I had lost my sense of direction and I was also afraid that, while I slept, the fire would advance.

Luckily I live in front of a stream that connects two lakes: Lake Gutierrez with Lake Nahuel Huapi, the largest in this region. The streams are firebreaks. In the book of the poet Graciela Cross that I read the other day she says: “A firebreak is a space of land that does not have any kind of fuel, so forest fires cannot spread.” There are natural, artificial, or created firebreaks. The natural ones are simply land with little or no vegetation, such as rivers; the artificial ones can be roads; and the created ones are made by the firefighters during the fire, by deforesting the selected area. The creek that runs in front of my house, not only prevents the advance of a fire, it also, as you say in your letter, prevents more houses from being built in that area—thanks to it I still have my view open and clear.

I wonder what is the firebreak in Gaza. What is the limit? How can we build a firebreak (cease fire?!)? I think the Mediterranean Sea on the shores of Gaza acts more as a firebreak than a firebreak. The other day, some friends of my mother’s who belong to the Jewish community (and who I assume are Zionists) told her that when the “war” was over they were going to move to Israel, because they like to live near the sea.

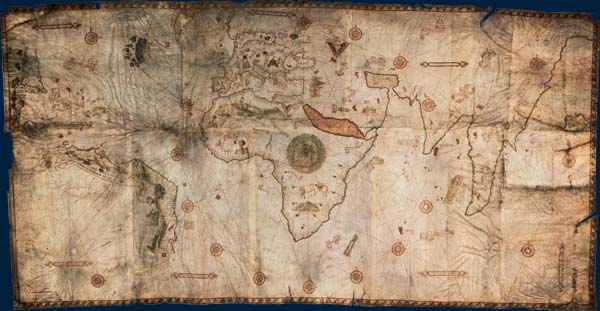

Sometimes I like to visualize territories through their water maps, to imagine how all the waters are connected, how they are all related. With my film I tried to link three important territories for my story through water circuits: starting with the multiple states of water in Bariloche (snow, streams, lakes, rains); going through the great Rio de La Plata in Buenos Aires, where my father died in an accident; and finally arriving at the Jordan River in the West Bank, the place where the meaning of my last name comes from: Gattas, which means “diver” or “baptism.”

I wanted to build an affective and aquatic audiovisual map. I was obsessed with thinking how to make these distant landscapes coexist visually and sonically. Between the Jordan River and the Rio de La Plata there are 12,896 kilometers of distance; between the Rio de La Plata and the stream in front of my house in Bariloche there are 1,594 kilometers. Although both territories, Palestine and Patagonia, share that they were—and still are—named as “deserts,” in order to be colonized, the vegetation, the colors of their landscapes are very different. Greens and blues predominate in my daily space, and earth colors and yellows do in the land of my ancestors.

While researching for my film, I searched through thousands of images on the internet about water in Palestine—downloading files on my computer is one of my favorite things to do, I can spend hours! In that frantic search I found these aerial photos within the Eric and Edith Matson Photographic Collection on the Library of Congress’ site:2

Some time later, in the General Archive of the Nation of Argentina, I found an audiovisual archive of the rivers of Patagonia; their aesthetic similarity seemed amazing to me and this video ended up being part of my film:

It seems that the connection with the Jordan River is not only visual, surfing the infinite rivers of the internet, I came across a fact that gave me goosebumps: the first name of the La Plata River was the Jordan River. The conqueror Amerigo Vespucci, in 1502, gave it that name erroneously.

From Maia

Letter 4: Fear of Forgetting

12-20 April, 2024, Santiago, CL and Amsterdam, NL

Hola Maia,

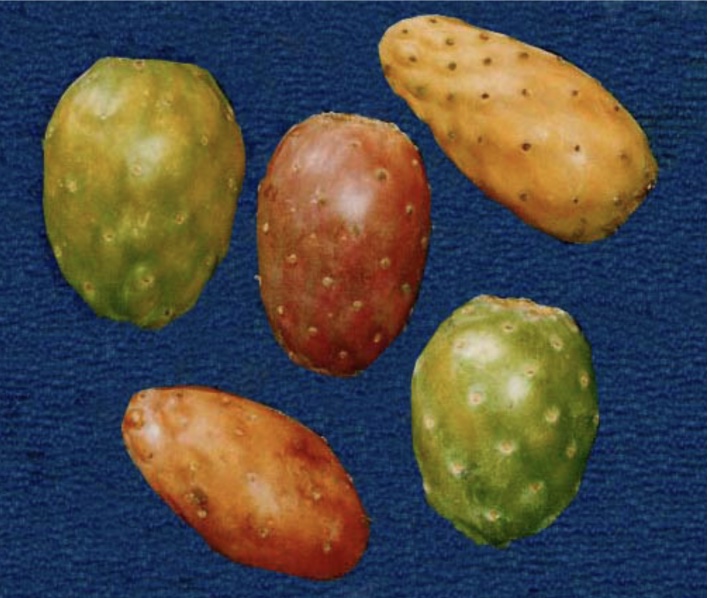

I remember the first fruit we tasted together. It seemed to be dragon fruit, but in my memory, it was also a tuna.3

This letter goes like this: it’s made from fragments of notes I’ve written to you and haven’t been able to put together into a coherent whole. I may resist the thought that these letters are being written to be published. I want to write to you, but I can’t help but think about those others who will access these texts and in what ways they will do so— translated into English and skipping parts. This fourth letter I write to you and me, y para nuestros recuerdos.

Today I want to archive two things: las tunas and my fear of forgetting.

When I read your letter and your reflection on the colors of the landscapes, I remembered a myth that is told here in Chile about the magnitude of the Palestinian diaspora.4 The usual question is: “Why Chile?” Once I was told that one of the reasons was the climate and the similarity in agriculture; in both places, cacti and tunas are harvested. Yesterday I ate the first tuna of the year that came from Tiltil. I Google the distance between Al Makhrour and Tiltil. It’s 13,225 kilometers of distance.

While we were eating it, we were watching the national news. The whole screen was red and orange. The fire consumes the territory, transforming the houses into ashes and rubble, and in my hand, coponcito de los Andes, bordada de agujitas, agua del desierto.5 Our cities burn and in my hand, there is a small spring, a natural firebreak.

Tuna corta fuegos. ¡Corten el fuego ya!

In Gaza, rainwater also belongs to Israel. In Chile, water has been privatized for decades. Today another piece of news hits us: the botanical garden of Viña disappeared. 200-year-old trees, a lagoon with fauna, trails in a Valdivian jungle, and precious eucalyptus: all burned to ashes.

If you touch the tunas they can damage your skin, but they keep and protect that which gives us life. Resisting and pricking seem to be inseparable.

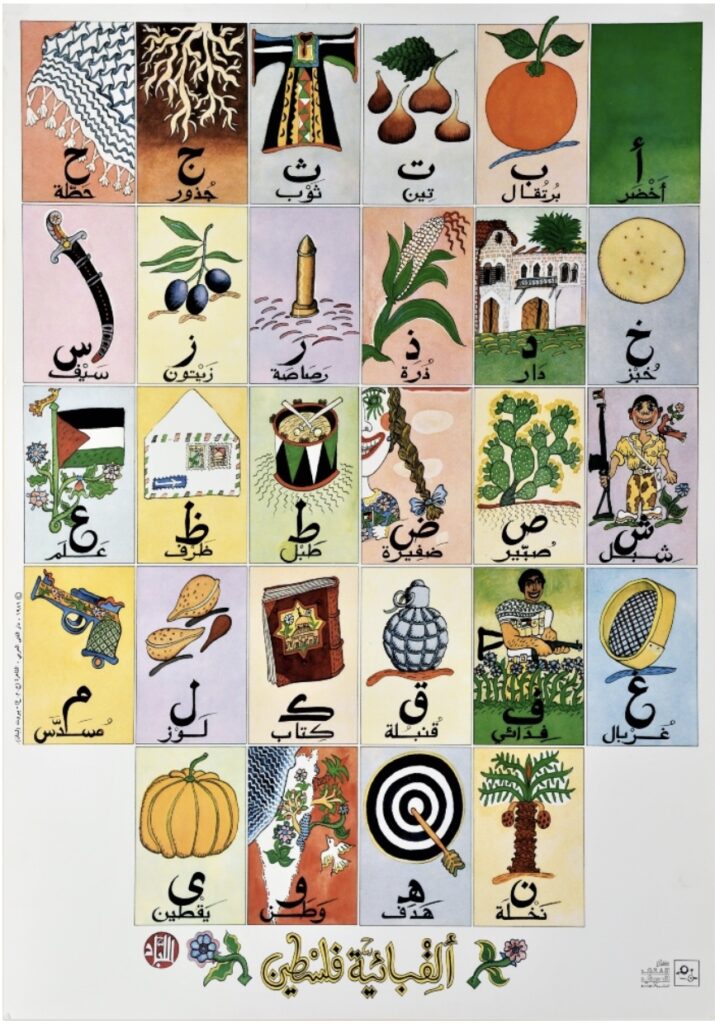

I was looking in the palarchive (of the Palestinian museum), and I found this poster of the Palestinian alphabet. There you see the drawing of a cactus to illustrate the letter «S» for «sabr» which in Arabic means patience or perseverance and has become a symbol of resilience for the Palestinian people.

In Chile we use the expression “Estar como tuna,” meaning: “To be like a tuna.” It is said to refer to someone who is in good condition, as if they have not been affected by the passage of time.

Who archives the work of the archivist?

In Palestine, I visited a place called Khazaaen, in Jerusalem, where Alaa Qaq opened the door for me. Khazaaen, she explained to me, means cabinets, and that’s what we have. Each person who contributes has a cabinet to store their legacy. This material preserves a collective memory of an entire community, revealing various historical facts and alterations throughout social history. The archive, conceived as water, changes the ground it passes through forever, and Khazaaen is the cactus that acts as a natural firebreak, preventing the passage of time from functioning like fire on memory, burning everything. Those cabinets save us from that fear of forgetting.

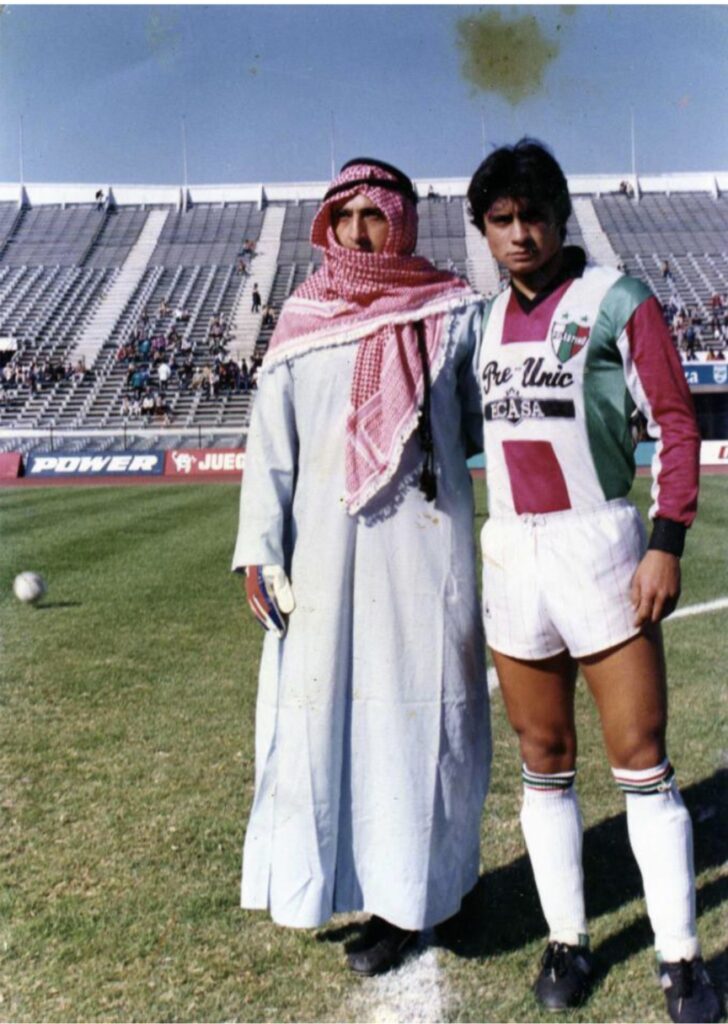

To end this letter, I want to take advantage of the public character we are giving to our letters, which will perhaps safeguard them from personal decisions to delete files. I am adding un capricho, one image that I want to keep under that blanket of thorns and water:

This image is one that I have already been saving in my hard drive for 13 years. The story goes like this:

In 1973, the Palestino Sports Club hired Manuel “Loco” Araya, a goalkeeper who became known for being a very eccentric character, as he constantly dressed up before entering the field. The moment captured in the this photograph is quite significant for several reasons. On the one hand, “Loco” Araya understands the importance of the identity of the Palestino soccer team to all of its supporters. This is because this institution is was one of the first in the world to use “Palestino” as a name, and to use the colors of the Palestinian flag. For this reason, the Palestino Sports Club is very significant to the entire Arab community in a way that goes beyond the barrier of sport, becoming a fundamental political identification. “Loco” Araya also understands that there is a stereotype of those who are part of this community and that this stereotype comes from the real clothing of those who first arrived in Chile and were discriminated against. It is interesting in the image how the footballers coexist with their uniform and “Loco” Araya is dressed as an Arab—also, which Arab? He generates a contradiction: He who dresses as an Arab is disguised as an Arab, and the footballer who dresses as such is a standard-bearer of that which became a fundamental political element to put Palestine on the map, being the first sports club in the world to be called Palestino and to use its flag.

“Loco” was not allowed to play that day. He was also known for peeling and eating an orange just before the matches, which caused the delay of the starting whistle.

Abrazos desde el norte,

Fran

Letter 5: My Handy Archives in Palestine 2019

27 March, 2024, Buenos Aires

Hi my friend!

This is my last letter:

Letter 6: Agua Santa (from My Handy Archives in Palestine 2019)

25 April, 2024, Amsterdam

Hola amiga,

Here is my last letter. Video archives from the time we met. I hope we meet again soon. It has been way too long, way too much water under the bridge.

Abrazos!

Fran

Maia Gattás Vargas

Visual artist, audiovisual creator, lecturer, and researcher.

PhD in Arts. Specialized in Latin American Contemporary Art (Universidad Nacional de La Plata).

She graduated with a degree in Communication Sciences and as a secondary and tertiary education professor (UBA).

She works as a postdoctoral fellow at CONICET and as a professor of Media and Culture Theories at Universidad de Buenos Aires.

She is currently developing her research project Indagaciones atmosféricas at the Medialab de Matadero, Madrid (2021-2025).

In 2022, she published her first artist book Diario de exploración al territorio del color, edited by Biblioteca Popular Astra de Comodoro Rivadavia.

Her first feature-length documentary Viento del este (East wind) premiered nationally in August 2023 at the Doc Buenos Aires Festival and internationally at the Jihlava IDFF in the Czech Republic, where it won the Original Approach award.

She has exhibited her visual and audiovisual works in different provinces of Argentina (Río Negro, Buenos Aires, Tierra del Fuego, Córdoba, Santa Fé and Neuquén), and in countries such as Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Canadá, and the Czech Republic.

She has been awarded the following prizes: Bienal de Arte Joven de Buenos Aires, 2019; Beca de Creación del Fondo Nacional de las Artes, 2022. Becar Cultura of the National Ministry of Culture, to attend the IV Encuentro Iberoamericano de Trabajo, Arte y Economía at the gallery Arte Actual of FLACSO, Quito, Ecuador. 2016.

Her artistic work explores the relationships between images, science, landscape, nature, and colonial history. She creates archival installations combining video, collage, photographs, documents, and writing.

Francisca Khamis Giacoman

Francisca Khamis Giacoman is a visual artist and designer based in Amsterdam. Through performances, installations, and audiovisual works, she recalls stories of migration and unfolds them at the boundaries of fiction and materiality. Her research touches upon language, knowledge production, and accessibility through narrative circulation, focusing on different ways of (re)membering ourselves and others.

Actively involved in self-organized projects, Francisca co-founded Museo del Perro * Honden Museum in Amsterdam (2023); Ediciones Rocas Shop Cooperative Publishing House in Santiago (2017–2022); C.I.A (Centro de Investigación Artístico) in Santiago (2013–2015); and Espacio Estamos Bien, an art cooperative in Amsterdam that curates gatherings, publications, and exhibitions. Currently, she leads the development of a support initiative for non-European students at Sandberg Instituut and Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam.

She has exhibited at Rozenstraat, Amsterdam; Extracity, Antwerp; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Kunstverein, Amsterdam; PuntWG, Amsterdam; Stroom, The Hague; Stadium, Berlin; Bibliotek, London; and Gold+ Beton, Cologne, among others.

- John Berger reads Ghassan Kanafani’s Letter From Gaza.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_msusYXQIfc ↩︎

- Eric and Edith Matson were photographers within The American Colony, 1881–1934. ↩︎

- Tuna refers to a prickly pear fruit or cactus fruit. ↩︎

- Palestinians in Chile (Arabic: فلسطينيو تشيلي) are believed to be the largest Palestinian community outside of the Arab world. There are around 6 million Palestinians living in diaspora, mainly in the Middle East. Estimates of the number of Palestinian descendants in Chile range from 450,000 to 500,000. ↩︎

- “Little cup from the Andes, embroidered with needles, water from the desert.” A phrase from Tuna Tunita by the poet Cayo Santos Huamán ↩︎

- https://palarchive.org/index.php/Detail/objects/233948/lang/en_US ↩︎